Recent findings from UNICEF’s review of child poverty in 39 OECD and EU countries show that child poverty has increased faster in the UK than in any other country investigated. Alec Haglund, IF Researcher, reflects on the results of the research and wider context of child poverty in the UK.

The numbers are worrying

The UNICEF Innocenti report card assesses the progress – or lack thereof – that 39 OECD and EU countries have made on child poverty. The time period covered by the report extends from 2012 to 2021, which means that some of the early impacts of the pandemic are accounted for.

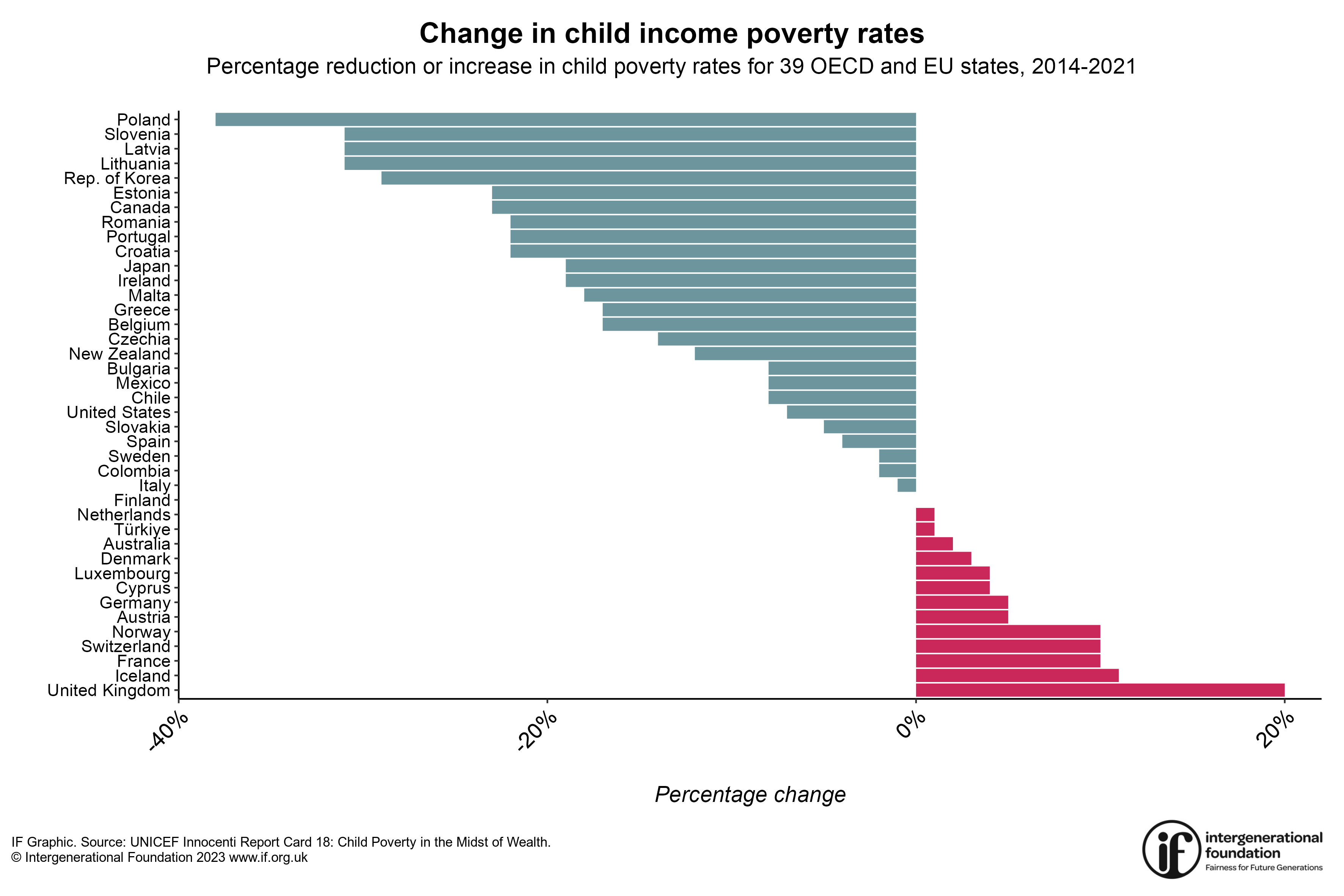

The majority of countries succeeded in reducing rates of child poverty over the time period covered, with Poland, Slovenia and Latvia topping the list for the highest reductions in child poverty. However, child poverty increased in 13 out of 39 countries, and the report found that 20.7% of children in the United Kingdom (UK) are now in relative income poverty.

UK at the bottom of the list

Out of all the countries investigated, nowhere did child poverty rates increase as fast as in the UK. The report found that child poverty rates had increased by 20% in the UK. This figure is extremely worrying, and much higher than the two other worst performers – Iceland and France – where child poverty rates increased by 11% and 10%, respectively.

The increase in child poverty over the period means that as many as half a million more children lived in poverty in the UK in 2021 compared to 2012. Child poverty rates in the UK are therefore the worst among the world’s wealthiest nations.

Reducing child poverty must be a policy priority

Given the period of rising wealth and economic growth associated with the years between 2012 and 2021, it is worrying that favourable economic conditions in the UK have not been translated into reductions in child poverty. The report makes clear that the UK did not take advantage of its fiscal headroom to reduce child poverty, unlike many other countries.

The UNICEF report also explains that high levels of wealth does not guarantee that a reduction in child poverty rates will follow. In fact, there is only a weak tendency for richer countries to have lower child poverty rates. Instead, nations must designate child poverty as a policy priority and commit sufficient funding and resources to fight child poverty and its root causes.

In the UK, children have been subjected to over a decade of cuts in government spending which has led to an increase in child poverty. The UNICEF report revealed that while the UK spent approximately 17% on cash benefits per child as a proportion of GDP per capita in 2010, this had fallen to just 11% by 2019.

Cuts to welfare spending pushes more children into poverty

Increases in child poverty cannot be reduced to a single issue. Rising housing costs, falling real wages and the cost-of-living crisis are all partly to blame, but it is clear that insufficient social security benefits and cuts to welfare spending have had damaging effects on the number of UK children living in poverty.

The two-child benefit limit, which limits benefits to the first two children, has led to nearly half of all UK children with two or more siblings living in poverty. Of those children living in poverty, 71% have at least one parent in employment, but cuts to Universal Credit have led to the social security system being unable to prevent in-work poverty from affecting children. The freezing of Local Housing Allowances, which link housing benefit to local housing costs, has meant that rapidly rising housing costs are pushing more children into poverty as housing benefit payments lag far behind the cost of renting.

On a local level, one out of ten large English councils are at risk of bankruptcy. An increase in the number of children needed to be taken into care, combined with soaring bills for children’s homes, are also contributing to financial pressures facing local authorities as 1 in 5 inch closer to insolvency. Many councils will soon be unable to provide crucial child protection services without urgent extra funding.

More must be done

One million children in the UK faced destitution in 2022, meaning that they cannot satisfy their most basic human needs such as staying warm, well-fed, dry, and clean. Not only is this an entirely unacceptable situation, but the fact that child poverty rates are increasing faster in the UK than in any other developed country means that we must urgently re-evaluate our political priorities.

Reducing child poverty must be put at the top of the policy agenda. This means that we must build an intergenerationally fair economy, where the needs of people of all ages are met. While this includes longer-term goals such as building more affordable housing, tackling climate change, and reforming the tax system, we must also take immediate action to improve the situation for children in the short term.

At the very least, the government must abolish the two-child benefit limit, uprate child benefit support, ensure real-terms increases in working-age benefits, and provide free school meals for all children without means-testing. While much more needs to be done, we should all call for the government to undertake these urgent reforms immediately. We want to see a country in which no child lives in destitution or poverty, and the Intergenerational Foundation will continue to hold the government to account when they fail to ensure that people of all ages are guaranteed a decent standard of living.

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate.

Photo by Jelleke Vanooteghem on Unsplash