The 2023 Autumn Statement did nothing to address intergenerational fairness and that was a missed opportunity by government. So what were the key policy announcements for April 2024 that might affect different generations? Daniel Harrison, economist, market analyst and author of Intergenerational Theft explains

The 2023 Autumn Statement did nothing to address intergenerational fairness and that was a missed opportunity by government. So what were the key policy announcements for April 2024 that might affect different generations? Daniel Harrison, economist, market analyst and author of Intergenerational Theft explains

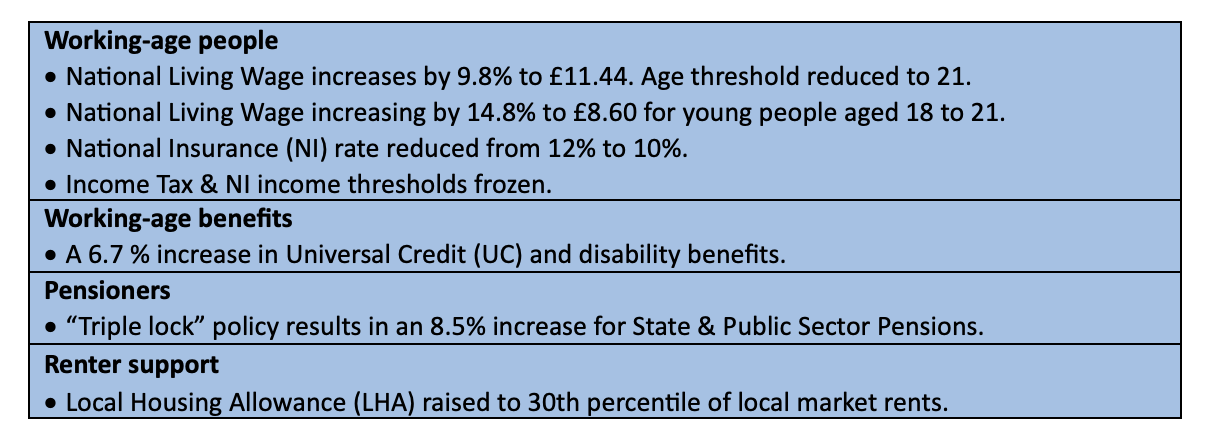

Autumn Statement announcements affecting different generations

Benefit increases may seem fair, but they’re not

On the face of it, it would seem that all generations are receiving benefit increases broadly in line with inflation, with increases for younger people in the National Minimum Wage (NMW), National Living Wage (NLW) Local Housing Allowance (LHA), and reduction in different types of National Insurance contributions (NICs).

However, the Autumn Statement hides a profound truth: All working-age people are still going to be paying higher taxes, further entrenching intergenerational inequality.

The paradox of rising taxes but declining public services

The Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) assessed that tax changes announced in the Autumn Statement reduced taxation as a share of the economy by 0.7%. However, in total, tax as a share of the economy is still due to rise “in every year to a post-war high of 37.7% of GDP by 2028/29.”

But there is a paradox. If taxes are rising, surely public services should be getting better? The economic reality is that those higher taxes are not going towards public services, but increasingly subsidising the debts of the baby boomer generation, as the Intergenerational Foundation has shown in its many pension reports on public sector pensions, and local government pensions’ reports. Furthermore, Michael Johnson, of the think tank the Centre for Policy Studies confirmed the bill for “vast unfunded promises” made to baby boomers, notably in state and public sector pensions, would be footed by the Millennial generation. Simultaneously, working-age people are receiving diminishing public services. For example, in the NHS, The King’s Fund described “the lowest level of satisfaction recorded since the survey began in 1983.” It’s not just a perception. It’s a reality.

Policy choices continue to favour the older generation

But most notably, the Autumn Statement retained the “triple lock” on the State Pension – a policy which even the Work and Pensions Secretary Mel Stride agreed was unsustainable “in the very, very long-term” whilst, in part, funding that policy commitment through welfare cuts.

It’s a stark economic reality predicted by the 2015 UK Parliament Select Committee for Work and Pensions stating “What research exists suggests that today’s young will be net contributors to the welfare state, while the baby boomer generation will be net beneficiaries. The effect is likely to have been exacerbated by policy decisions to protect pensioner benefits while targeting welfare cuts on working age payments. The limits of that approach have been reached.”

Intergenerational unfairness: The facts

Let’s quickly examine the wider context here: Within the UK, longstanding policy biases have increasingly favoured older voters, which have deeply entrenched intergenerational unfairness.

The last major independent analysis based upon “generational accounting” was conducted by the 2015 UK Parliament Select Committee for Work and Pensions concluding “The economy has become skewed in favour of baby boomers and against millennials.…People currently aged 65–69 would on average have a net withdrawal of more than £220,000 over the remainder of their lifetimes. In order to achieve fiscal balance by the end of today’s infants’ lifetimes, as yet unborn people would each need to contribute an average of £160,000 in net terms.”

Older people have not paid enough tax

Older people, primarily baby boomers, have not paid enough tax, instead they have accumulated national debt, and are now withdrawing even more in pensions than they paid in. Fundamentally, the government’s Autumn Statement does nothing to address this deeply entrenched intergenerational inequality.

Housing market continues to fail young people and the economy

But even more profoundly, there was no attempt to address the elephant in the room: the housing crisis, which burdens young people with unprecedented housing costs, delaying natural milestones such as moving out, buying a home, or starting a family.

The Chancellor kept saying how important economic growth was, and yet deliberately ignored the blindingly obvious link between overinflated house prices and low investment leading to low growth.

Our dysfunctional housing market locks so much unproductive capital (around £8.7 Trillion) in bricks and mortar and that is toxic for our economy. Take buy-to-let properties: imagine instead if investors invested that capital more productively in businesses that actually created jobs and grew the economy. Reduced housing costs would also allow young people to spend more of their disposable income driving economic activity. Therefore, house price increases should be viewed as suffocating the economy, rather than a source of celebration.

But why won’t the government tackle the housing crisis?

Fundamentally, rocketing house prices over the past 40 years have pandered to the older homeowning generation, particularly the larger boomer cohort, making them incredibly asset rich – but at the expense of the young – driving an estimated wealth transfer from young to old of £3.9 Trillion. Any attempt to set housebuilding targets and bring house prices down are met with howls of protests by NIMBYs. Whilst government panders to older homeowning voters, the housing crisis is a problem it simply doesn’t want to solve.

Call to action

Fundamentally, what we desperately need in the UK are far more imaginative policies to address intergenerational unfairness – and to allow our younger people to flourish and reach their full potential, which is not only fairer, but it’s also sound economics that is good for the country as a whole, not just for a narrow, largely older demographic.

Daniel Harrison is an economist, and author of the book ‘Intergenerational Theft’

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate.