The disease itself may have touched Australia relatively lightly, but the wider consequences have hit the young particularly hard, especially in employment. Danielle Wood and Owain Emslie, CEO and Senior Associate respectively at the Grattan Institute in Melbourne, reveal the facts and figures, and the broader patterns that underlie them.

Australia has avoided the worst of the COVID-19 health crisis so far. As at the end of June, there had been about 8,000 coronavirus cases and 104 deaths among a population of 25 million Australians. This is a much lower rate of infection than most other countries. Australia’s geographic isolation was an advantage, as was our fast and effective adoption of lockdown laws.

But Australia has not been similarly spared from the economic crisis. GDP fell 0.3% in the March quarter, and will be much lower again in the June quarter. About 7.5% of all jobs disappeared between 14 March and 30 May. Australians worked 10% fewer hours in May than in March.

Unlucky for the young

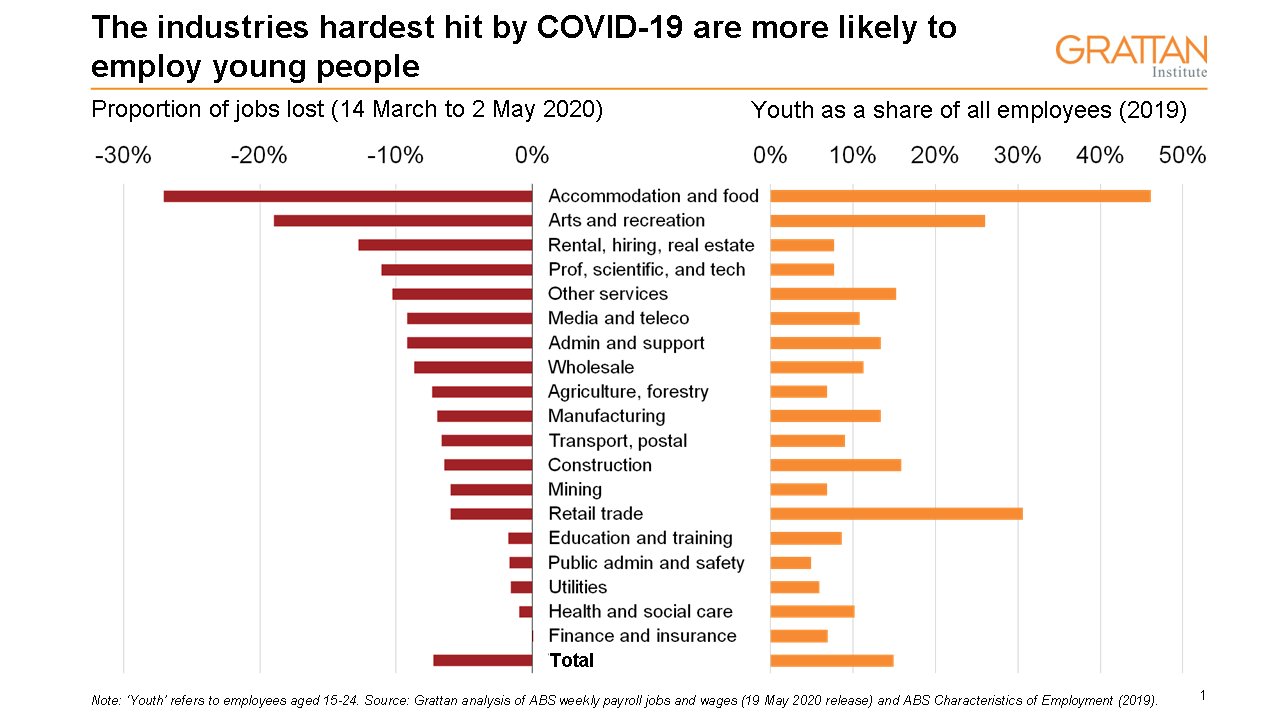

Young workers have borne the brunt of the job losses. The businesses most affected by social distancing restrictions are those most likely to employ young people – restaurants, bars, retail outlets, gyms, and recreation and tourism businesses (see Figure 1).

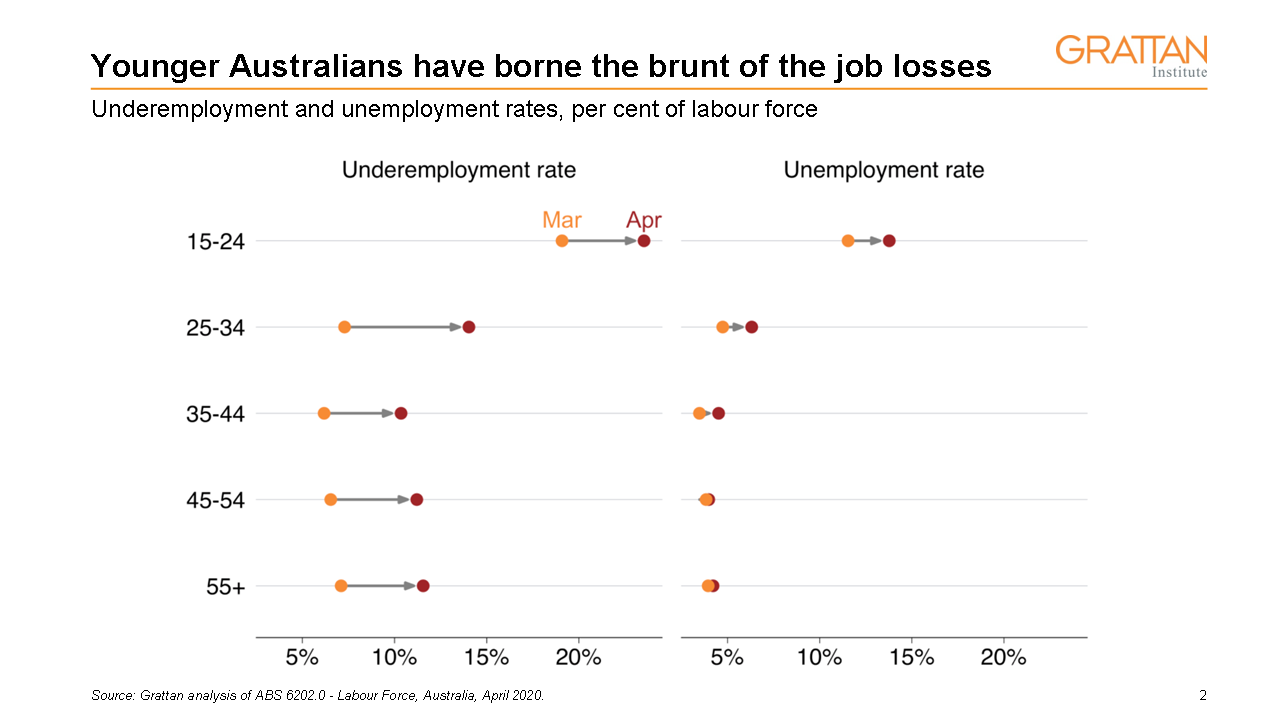

Youth unemployment rose to 13.8% in April – double the headline unemployment rate (Figure 2). With more than 20% of Australians aged 15–24 also underemployed, more than one in three younger Australians were without paid work or working fewer hours than they would like to.

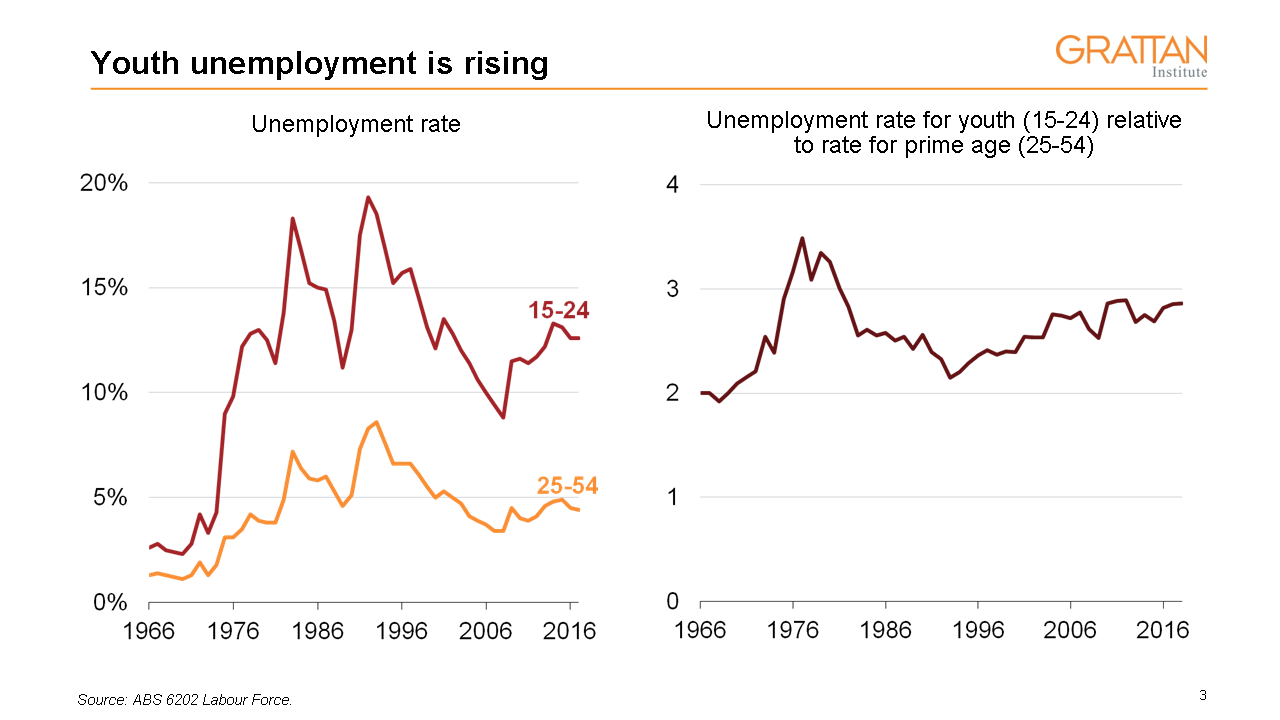

Youth unemployment is always higher than general unemployment. The gap tends to widen during economic downturns and narrow when employment markets are strong. Young people tend to be the marginal employees – when employment demand is soft, employers are more likely to keep their existing (older) employees and not hire the same number of new (younger) employees.

But even before the COVID crisis, unemployment and underemployment were high for young Australians. The gap between youth (aged 15–24) employment and “prime age” (25–54) employment in Australia has been growing since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) and was above the OECD average pre-COVID. A study comparing pre- and post-GFC cohorts of young Australians revealed that even among those who found employment, the post-GFC cohort had less job security, fewer hours of work, and lower earnings.

Mind the gap

The economic gap between young and old was already large and growing – in incomes, wealth, and spending. The danger now is that the COVID crisis could substantially exacerbate intergenerational inequality in Australia.

The generation who are making the transition into employment at a time when fewer jobs are being created will be especially disadvantaged. Young people who graduate during recessions typically suffer long-term consequences, with worse average labour market outcomes over their lifetimes than cohorts that graduate into booming labour markets. A recent study estimated that a 21-year-old today will earn $32,000 less over the coming decade as a result of entering the workforce during a recession.

Short-term remedies

Australia’s governments have helped to soften the blow, at least temporarily, through additional financial support for job seekers and the “JobKeeper” wage subsidy scheme. Announced in late March as a six-month scheme, JobKeeper gives $1,500 per fortnight to affected businesses for each employee they keep on the books. The new payment is close to 70% of the typical (median) wage in Australia. The real advantage of this scheme, unlike those adopted by the UK and across Europe, is that affected businesses receive the payment for all employees, including those still working.

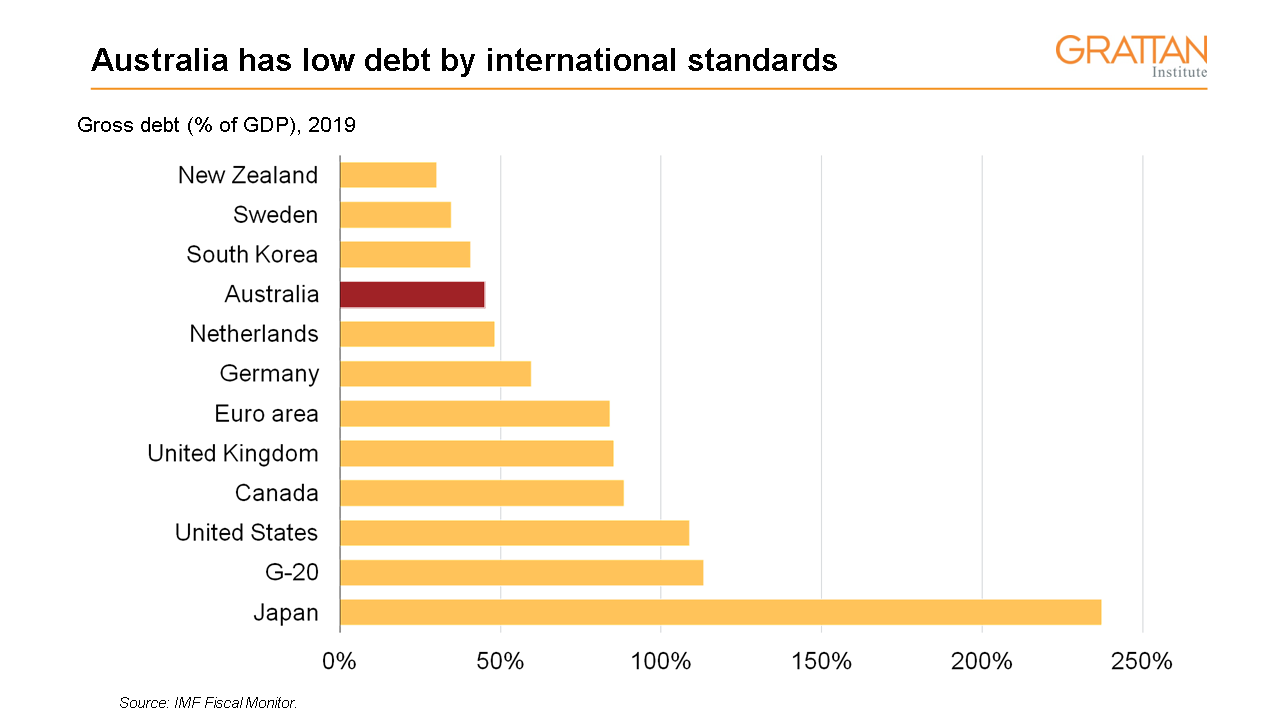

In total, the Australian Government COVID crisis fiscal stimulus to date is equivalent to about 7% of GDP – comparable to other developed nations. And Australia has the fiscal space to borrow further to support the economic recovery, having come into this crisis with low debt levels by international standards (Figure 4).

The biggest concern is that Australian governments will attempt to consolidate their budgets too soon. This would put a hand-brake on the economic recovery, hurting job prospects particularly for younger people.

Risk of a double hit – could be averted

When the economy is back on track, Australian governments will need to tackle structural budget challenges. The risk here is that the burden falls disproportionately on the same generation that is bearing the cost of the shutdown at present. For example, if all the hard work is done through creeping income tax collections, young people will pay twice: first in the initial employment shock, and second with a higher tax burden through their careers.

Fiscal consolidation over the medium-term should ensure that comfortably-off older Australians pay their fair share. Winding back some generous tax breaks for older Australians that serve little policy purpose would be a better way to ensure that the economic cost of the coronavirus doesn’t just fall on the shoulders of the young.

Ultimately, the best way to get debt under control is to increase the size of the economy over time – and this would benefit younger generations especially. Healthy GDP growth allows debt to shrink as a share of the economy without the need for tax increases or spending cuts. It remains to be seen whether Australian governments have the appetite for the economic reforms that would help achieve this.

Even before the COVID crisis, Australia was at risk of leaving a generation behind. That risk is now heightened but, with the right policy reforms, the young need not foot the entire COVID bill.

Image: detail of “The Guardians” sculpture by Simon Rigg, Southbank, Melbourne. Photo by Mitchell Luo on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/@mitchel3uo