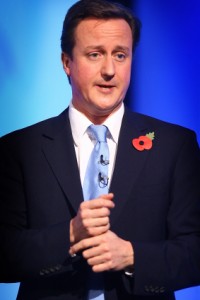

With barely 10 weeks to go until the 2015 general election, Prime Minister David Cameron has pledged to keep all universal benefits for pensioners if he remains in power

The Prime Minister David Cameron has pledged to retain support for all universal pensioner benefits if he remains in power after the 2015 general election, which looms in little over 10 weeks’ time.

“Done the right thing”

Mr Cameron gave a speech on 23 February in which he reiterated an argument he has used before – including on the campaign trail before the last general election in 2010 – that pensioners deserve special treatment in recognition of all the good work they have done on behalf of society during their earlier working lives:

“In 2010, I looked down the barrel of the camera and made a clear commitment to the British people that I would keep these things [universal benefits]. And that wasn’t a commitment for five years – it was a commitment for as long as I was prime minister.”

“If you’ve worked hard during your life, saved, paid your taxes, done the right thing, you deserve dignity when you retire. These people have fought wars, seen us through recessions – made this the great country it is today. They brought us into the world and cared for us, and now it’s our turn – our fundamental duty – to care for them.”

Can we afford it?

The problem with Cameron’s argument is that it ignores the issues of affordability and fairness, both of which are big challenges.

This was neatly summarised by a piece of research from the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS), published last November, which argued that the cost of providing pensioner benefits will rise by roughly £12 billion a year by 2020, despite the fact that “pensioners as a group have stopped being poor,” according to the researchers.

They found that in 2011, for the first time since the creation of the modern welfare state, average pensioner incomes were higher than those of working-age households once the costs of housing and children were taken into account. In a separate piece of research, the IFS has also found that people retiring today are likely to be better-off on average during their retirements than they were during the course of their working lives.

The scale of the change in pensioner incomes is shown by the fact that in 1990 over 40% of pensioner households could be classed as living in poverty, but now it is down to just 15%. It is also worth remembering that these comparisons were only looking at incomes; comparing overall wealth would show that today’s pensioners have done even better, as many of them have benefited from rising house prices and generous defined-benefit pension schemes to a degree which their children and grandchildren can only dream of.

Paul Johnson, the director of the IFS, argued that the Coalition ignored these trends in the shifting patterns of poverty between people of different age groups when crafting their austerity programme:

“Those currently retired and those hitting state pension age over the decade have been spared most of the effects of austerity, at least in terms of their incomes.”

This means that most of the pain has fallen on younger households, especially in terms of welfare reductions; only the week before he made his announcement about pensioner benefits, Mr Cameron’s party announced that support for young jobseekers would be retrenched even further, to the point where they could have to spend 30 hours a week working on community service-type projects to receive support payments worth less than the minimum wage.

In an ideal world, all age groups would get the amount of help they need from the state to live their lives with dignity. But in a situation where resources are as limited as they are now, protecting one group means taking from another – and it should come as no surprise that the group which is being protected are the ones who are more likely to vote.