IF supporter Tim Lund explains why the current focus on demand-side measures hurts both the younger generation and the broader economy

The problem with most of the current economic policies from both the government and the opposition (Ed Balls recently provided the latest example of this trend) is that they are dominated by demand-side thinking – e.g. a call for “urgent” action on growth, leading to short-term measures which are supposed to “kick-start” the economy; for Ed Balls it’s a stamp duty holiday, for George Osborne it’s a temporary relaxation of planning controls.

They are both right to view construction as a viable source of growth, but both are wary of tackling the supply-side problems which have resulted in persistently low levels of house building. This will be for two reasons. First, understanding the supply side of the economy is much harder – you need a real understanding of the factors which lead people to invest, or not. It is much easier to stick to arguments about the demand side, positioning yourself – as does Ed Balls – as calling for more growth.

The other reason for evading the construction supply side is that it is all too painful, and in particular that sorting it out will mean a comparable hit to the demand side of the economy as it endured during the banking bust of 2008. In fact, it is unresolved business from that era.

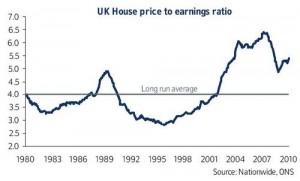

The overwhelming fact is that, thanks to the lack of supply, house prices and rents are way higher than they should be, and investors know it. In such circumstances, investors are never going to be keen to invest more, since they are likely to see the value of their investments fall. That favourite idea of politicians – encouraging first-time buyers, as Ed Balls wants to do with his stamp duty holiday – will be just another way of loading people in the 20s and 30s with debt, in parallel with other current policies such as student loans.

What has to happen is for the value of property to fall enough to attract investors – that really is all. There are loads of people who want new places to live, and there are billions locked up in pension funds (and other investment vehicles), looking for something offering better returns than 50 year loans to the government offering 0.04%.

The downside is that this sort of price correction will severely damage the balance sheets of our conventional financial institutions – the banks and building societies who lent all that money to current homeowners in the run-up to 2008. It will cause severe short-term pain, but the alternative – something like the decades of stagnation Japan suffered following the collapse of its stock market – is much worse.

And it will particularly hurt the younger generation, because with conventional lenders rebuilding balance sheets overextended into loans to their elders, 20-somethings are left to be targeted by pay day lenders.

What has gone wrong with a the housing supply side is another – and complex – matter which we hope to return to…