Thomas Brookes looks ahead to IF’s Youth Manifesto essay competition (deadline 1 October!) and maintains that it is vital for the young to fight their corner, even in the face of neglect from policy-makers

In early 2015 each of the political parties vying for votes in May’s general election will publish their manifesto. Each will surely come clad in an intriguing cover, headed by a meaningless title and accompanied by idealistic jargon, but their primary purpose is this: to present policies which will attract voters.

An unrepresented minority

Yet there is one significant section of society – who comprise 40% of the population – who are unlikely to be catered for: young people. While pensioners enjoy universal benefits such as free transport and the winter fuel allowance, and are afforded more concessions in successive manifestos and budgets, the young rarely receive any targeted policies. This effectively demonstrates that those currently drafting their party manifestos are more interested in securing seats than solving problems.

Two things are clear. First, that the older generations are more reliable and influential voters than the young. In 2010, following the trend of all recent elections, 74.7% of the over-65s voted, compared to only 51.8% of those aged 18–24. If a parliamentary candidate can entice the votes of the old with a flutter of the electoral eyelashes and a flash of advantageous benefits, therefore, then the reliability of pensioners making it to the polling station can go a long way towards winning the seat. Moreover, although many constituencies have high proportions of young voters, these tend to be students, whom politicians can disregard due to the lower probability of them voting and the lower probability of them remaining in the constituency for an MP’s pursuit of re-election five years on.

The second truth is that politicians not only court the elderly vote in the run-up to the election, but also throughout their terms of office, resulting in policy which unfairly prioritises the needs of the old. Just earlier this year, for instance, the Government’s Spring Budget resembled little more than a succulent honey trap used to lure greying voters. The budget lowered tax and removed restrictions on pensions, offered a tax-free savings limit which would largely benefit the old and the rich, and finally, in a transparent bid to attract elderly voters which verged on the satiric, cut bingo duty by half. Policies which failed to be introduced were any measures whatsoever to help the 868,000 16–24 year olds without a job, or even those in employment whose wages have fallen at a greater rate than any other age group. Unless, of course, the Government has identified a constituency in which the vote can be swung by teenage bingo enthusiasts, it is clear that the budget was not intended for the young.

A unique chance for the youth voice to be heard

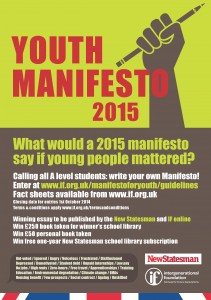

Thus young people may seem to be caught in a bind: unlikely to attract targeted proposals and policy due to low voter turnout, but unlikely to turn out to vote in greater numbers unless motivated by policy. It is in light of this situation that the Intergenerational Foundation and the New Statesman have asked “What would an election manifesto say if young people mattered?”

This competition gives sixth-formers the chance to answer this question with ten policy proposals of their own. Excitingly – and unusually, given the customary disregard of young opinions in the media – the winning entry will be published in the New Statesman, a magazine with a national circulation of above 25,000. There are also the expected monetary bribes – sorry, prizes – of £50 book tokens for the winner and the runners-up. Finally, the school libraries of the winner and the runners-up will receive book tokens worth £250 and £150 respectively. Subtext: any teachers or librarians reading this, wield your influence to coerce students into applying.

This is a fantastic opportunity for any young person to experiment with ideas, respond to injustices and take on a challenge usually reserved for members of the Westminster bubble alone. Ten policy proposals are a healthy amount: hopefully not too many to seem daunting, but enough to allow your suggestions to range from the radical to the pragmatic, the expansive to the specialised, the expensive to the profitable.

Getting started

Applicants should, of course, feel uninhibited when presenting their proposals, but here are some suggestions for what to consider and how to get started.

One approach, in a bid to seize the issue of intergenerational injustice by the throat, may be to deal with the fundamental issue of the voting deficit between younger and older generations. Applicants may wish to deal with this in a number of ways. Would you lower the voting age to 16, as has been introduced for the Scottish referendum and proposed by Labour? Or perhaps introduce compulsory voting, as has been the case in Australia for almost a century? Or, disregarding the overwhelming verdict of the 2011 AV referendum, applicants may wish to try once more to do away with our first-past-the-post voting system.

Beyond this potential starting point, there is no shortage of pressing issues affecting young people which young manifesto-writers may wish to tackle. The job market, for instance, is saturated, leaving young applicants with little space to turn. This affects all young people, from those with no qualifications through to recent graduates, and has resulted in a youth unemployment level of 16.9% for 16–24 year olds. This is an issue which ought to be tackled, and a Youth Manifesto is as good a place as any to begin the conversation.

Even those with jobs, however, are likely to struggle to find adequate housing, the rising price of which has resulted in almost two million prospective first-time buyers unable to afford a home, in stark contrast to the ease with which previous generations could get a foot on the housing ladder. Does the UK need to invest in more new-builds? Replenish its low stock of council housing? Or seek alternative remedies altogether?

Whichever direction you choose to take the Youth Manifesto – whether it answers these questions, disputes their importance, or ignores them entirely in favour of the legions of other issues facing young people – remember to be bold in both your ideas and your presentation of them. And good luck.