Academic Prizes: Archive

The Foundation for the Rights of Future Generations (FRFG) and the Intergenerational Foundation (IF) jointly promote and award two biennial prizes, in alternate years: the Demography Prize and the Intergenerational Justice Prize. A total of €10,000 – generously endowed by the Stiftung Apfelbaum – is awarded each year and divided among the winning entrants.

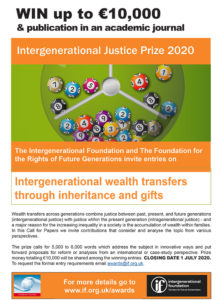

Intergenerational Justice Prize 2020

Write an essay on:

“Intergenerational Wealth Transfers through Inheritance and Gifts”

***DEADLINE EXPIRED 1 JULY 2020***

The Stuttgart-based Foundation for the Rights of Future Generations (FRFG) and the London-based Intergenerational Foundation (IF) jointly award the biennial Intergenerational Justice Prize, endowed with EUR 10,000 (ten thousand euros) in total prize-money, to essay-writers who address political and demographic issues pertaining to the field of intergenerational justice. The prize was initiated and is funded by the Apfelbaum Foundation.

Aim of the competition

Through the prize, the FRFG and IF seek to promote discussion about intergenerational justice in society, and, by providing a scholarly basis to the debate, establish new perspectives for decision-makers. The invitation to enter the competition is extended especially to young academics from all disciplines.

For the 2020 prize, the FRFG and IF call for papers on the following topic:

“Intergenerational Wealth Transfers through Inheritance and Gifts”

Prizes

The Intergenerational Justice Prize is endowed with EUR 10,000. The prize money will be distributed proportionally among the best submissions, which can be more or less than the top three submissions. Winning submissions will be considered for publication by the editorial team of the Intergenerational Justice Review (IGJR; www.igjr.org) for the summer issue 2021.

Closing date for prize submissions: 1 July 2020

Eligibility

- Researchers from all fields of social science, especially young researchers (students, graduates, post-docs). There is no age limit. Collaborative submissions are also welcome.

Entries

- can be submitted in either English or German

- should be 5,000 to 8,000 words in length (excluding figures, tables and bibliography)

For full entry requirements (details of required formatting, addresses for submissions etc, and an official entry form) email Antony Mason at [email protected]

Topic abstract

Wealth transfers across generations combine justice between past, present and future generations (intergenerational justice) with justice within the present generation (intragenerational justice).

For questions of intergenerational justice, with inheritance and legacies it is not the transfers between deceased persons and the survivors of the same family generation (widow, siblings) that are relevant, but between deceased persons and the next generation(s), i.e. the children or grandchildren. A major reason for the increasing intragenerational inequality in a society is the accumulation of wealth within families.

When someone dies, there is an opportunity to mitigate this effect. The essential instrument for this is an inheritance tax. To varying degrees, inheritance tax deprives the testator of the opportunity to pass on their assets to their direct descendants. Instead, the state distributes it to all citizens.

In order to counteract a possible avoidance of inheritance tax through donations before death, the state can levy a gift tax. Both types of tax are, of course, politically highly controversial.

Inheritance (and gifting) only arises as a “philosophical problem” when property rights are individualised. On the one hand, there is the view that the acceptance of private property implies that it should also be allowed in family relationships: wealth may accumulate along family lines, instead of being redistributed to society as a whole at every change of generation. Conversely, the birth lottery (the question of being born into a poor or rich family) should not affect the life chances of the youngest generation. According to this latter view, the right to inheritance should be rejected because it enables the heirs to have an unearned and effortless income and reduces the relative opportunities of the familially and financially underprivileged.

To date, no liberal-democratic constitutional state has completely eliminated this effect. Some countries, including Switzerland and Sweden, do not levy taxes on inherited property at all. One reason for this is the impact of inheritance tax on family businesses. A high inheritance tax on all business assets would lead to the expropriation or forced sale of businesses if the previous owner dies. A further reason consists in the difficulty of monetising the wealth of real estates. These values quickly exceed possible allowances, with the result that the children may no longer be able to live in their parents’ house.

Undoubtedly, intergenerational transfers of wealth by inheritance and gifts (and related issues of inheritance and gift tax) are a complex issue that has been the subject of many political and philosophical discussions. In this Call for Papers we invite contributions that consider and analyse the topic from various perspectives of intergenerational justice.

Scope

The Intergenerational Justice Prize 2020 aims to illuminate and analyse the role of intergenerational wealth transfers for intergenerational justice. Entries to the competition could approach the topic through a broad range of questions, including:

- Is it legitimate for wealth to remain within families, generation after generation? Should the children of the deceased person be able to inherit all his or her wealth; or should the wealth be taxed by the state, for greater redistribution? Which philosophical arguments speak in favour of the dynastic approach, which ones support the societal approach?

- To what extent do inheritance (and gift) tax systems differ in terms of tax rates and allowances according to degree of kinship in OECD countries or beyond? Are there fluctuations over time? How are business assets handled? How much money do these taxes generate for the tax authorities? What percentage of the population is liable to these taxes?

- What undesirable and negative economic side effects can be observed in the various tax systems? Do inheritance and gift taxes have an influence on financial planning and affect behaviour?

- How (un)popular are (high) inheritance and gift taxes among voters? Can this topic be used to win elections? Are there different opinions depending on age/generation?

- Do the attitudes towards inheritance taxation differ in different countries and between different social groups? Are there connections between the type of political system, political culture and/or socio-demographic composition and development of society on the one hand and the existence and level of inheritance tax on the other?

- How does inheritance tax relate to the welfare state? Does a higher inheritance tax empirically actually lead to less inequality?

- Which relevant narratives and argumentation strategies can be identified in politics, business, society and the media, and where do they converge?

- Inheritance taxation has developed very differently in the various legal systems, with considerable legal differences. What relevant rulings of constitutional courts exist on this subject? Is there a connection between the different legal cultures and the question of inheritance tax in an international comparison?

- What role do questions of intergenerational justice play in the evolution of relevant laws and in relevant court rulings? What should an intergenerationally just inheritance tax law look like?

- Each developed country has had key moments in the political and legal histories of the taxation of inherited wealth. What can historians tell us about this topic?

Note that these are non-binding suggestions: participants are strongly encouraged to come up with their own research puzzles. You may adapt the title according to your chosen subject, but the paper must in essence reflect the topic.

The submitted papers should be innovative, creative and with a focus on civil society issues, with practical applications. The FRFG and IF particularly appreciate participants trying to explain complex ideas in as simple and accessible terms as possible. Submitted research papers may employ all possible methodological approaches.

Demography Prize 2019

Write an essay on: “Housing Crisis: how can we improve the situation for young people?”

***DEADLINE EXPIRED 1 DECEMBER 2019***

The Stuttgart-based Foundation for the Rights of Future Generations (FRFG) and the London-based Intergenerational Foundation (IF) jointly award the biennial Demography Prize, endowed with EUR 10,000 (ten thousand euros) in total prize-money, to essay-writers who address political and demographic issues pertaining to the field of intergenerational justice. The prize was initiated and is funded by the Apfelbaum Foundation.

Aim of the competition

Through the prize, the FRFG and IF seek to promote discussion about intergenerational justice in society, and, by providing a scholarly basis to the debate, establish new perspectives for decision-makers. The invitation to enter the competition is extended especially to young academics from all disciplines.

For the 2018/2019 prize, the FRFG and IF call for papers on the following topic:

“Housing Crisis: how can we improve the situation for young people?”

Prizes:

The Demography Prize is endowed with EUR 10,000. The prize money will be distributed proportionally among the best submissions, which can be more or less than the top three submissions. Winning submissions will be considered for publication by the editorial team of the Intergenerational Justice Review (IGJR; www.igjr.org) for the summer issue 2020.

Closing date for prize submissions: 1 December 2019

Eligibility:

- Researchers from all fields of social science, especially young researchers (students, graduates, post-docs). There is no age limit. Collaborative submissions are also welcome.

Entries:

- can be submitted in either English or German

- should be 5,000 to 8,000 words in length (excluding figures, tables and bibliography)

Topic abstract

In many European countries, and especially in large cities and university towns, affordable housing is a pressing and sometimes explosive issue.

In the debate about such questions as home ownership or rent increase caps, the intergenerational perspective is often forgotten. But different generations are affected in noticeably different ways. Rising rent and purchase prices make it ever more difficult for young people to access the housing market. The quality of housing is a key factor in living standards and wellbeing, as well as an integral element of social integration, yet in 2014 a total of 7.8% of young people in the European Union (aged between 15 and 29) were in severe housing need, 25.7% of the young people in the EU lived in overcrowded households, and 13.6% lived in households that spent 40% or more of their equivalised disposable income on housing (Eurostat 2016). Young people often live longer in their parental homes, or in the private rental sector, than previous generations (Ronald/Lennartz 2018).

In response to the 2008/9 financial crisis, government programmes for public and social housing aimed at the poorer parts of the population were cut back, leading to diminishing access to affordable housing, especially in urbanised areas. For young people, this means that they have to pay higher rents.

What is often referred to as a “housing crisis” can certainly be seen as a question of intergenerational justice, because the baby boomers had easier access to housing or to the means to finance it. Today, the baby boomer generation benefits from housing inequality in two ways: through property values and rental income. At the same time, with pension systems under pressure because of ageing populations, the ownership of residential property has become an important component of retirement income (Helbrecht/Geisenkauser 2012).

Younger generations, on the other hand, are disadvantaged in two respects: today’s increased demand leads to further pressure on the housing market in the low-price segment, which in turn leads to an increase in the rent burden for lower and middle income groups, and also makes the purchase of residential property more difficult. In many parts of Europe, such as the Southeast of the UK, in the 1980s the average cost of a first home was three to four times the annual average salary; today it can be ten or twelve times the annual average salary.

In many European countries, ownership of real estate has become a much greater source of wealth inequality between generations than salary differentials.

This gloomy picture of housing and home ownership is, however, by no means universal. Statistics point to significant differences between countries, and international comparisons show that successful housing policies are possible. An EU comparison shows that the percentage of households managed by a person aged 18–29 who spends 40% or more of their disposable income on housing costs ranges from 1.3% (in Malta) to 45.4% (in Greece) (Leach et al. 2016). It is clear that some countries perform significantly better than others in providing affordable housing for the next generation.

Scope

The Demography Prize 2018/19 aims to illuminate and analyse the housing situation of the young generation. Entries to the competition could approach the topic through a broad range of questions, including:

- How did the housing crisis come to be and how can housing inequality for young people be improved? What weight do different factors (such as demographic shifts, changing preferences, market or government failures) have?

- Why are some countries better than others at providing affordable housing for the next generation? What are the similarities and differences? What lessons can be drawn from cross-country comparisons?

- Planet vs. people: It is often suggested that the solution to the housing crisis is to build more homes, but this raises the question of encroaching on green spaces and the environmental impact that this implies. How can that tension be resolved? How can urbanisation and the housing market become more environmentally friendly?

- What political levers, such as subsidies, could be introduced to help the younger generation achieve more affordable and long-term housing security? Is the German debt brake (Mietpreisbremse) a successful instrument for this and how does it affect the young generation?

- What is the potential of new forms of housing, such as shared housing, multi-generational housing, homeshare (accommodation offered in exchange for help and/or companionship)?

- Can government policy help to bring about new usage patterns of the existing house stock, for example by incentivising the fuller occupation of large houses with unused spare bedrooms, or by discouraging the ownership of second homes through higher taxation?

- How does homelessness affect young people in particular and how can it be combated?

- How can those who work in the media be encouraged to address this topic?

Note that these are non-binding suggestions: participants are strongly encouraged to come up with their own research puzzles. You may adapt the title according to your chosen subject, but the paper must in essence reflect the topic.

The submitted papers should be innovative, creative and with a focus on civil society issues, with practical applications. The FRFG and IF particularly appreciate participants trying to explain complex ideas in as simple and accessible terms as possible. Submitted research papers may employ all possible methodological approaches.

Literature cited in the text above

Eurostat (2016): Young people – housing conditions. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/46039.pdf. Viewed 27 September 2018.

Ronald, Richard / Lennartz, Christian (2018): Housing careers, intergenerational support and family relations. In: Housing Studies, 33 (2), 147-159.

Helbrecht, Ilse / Geilenheuser, Tim (2012): Demographischer Wandel, Generationeneffekte und Wohnungsmarktentwicklung: Wohneigentum als Altersvorsorge? In: Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 70 (5), 425–436.

Literature suggestions

Dorling, Danny (2015): All That is Solid: How the Great Housing Disaster Defines Our Times, and What We Can Do About It. London: Allen Lane.

Dustmann, Christian / Fitzenberger, Bernd / Zimmerman, Markus (2018): Housing Expenditures and Income Inequality, Cream Discussion Paper 16/18, London: Centre for Research and Analysis of Migration, URL: http://www.cream-migration.org/publ_uploads/CDP_16_18.pdf. Viewed 24 October 2018.

Eurostat (2016): Young people – housing conditions, https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/pdfscache/46039.pdf. Viewed 27 September 2018.

Eurostat (2015): Housing cost overburden rate. http://appsso.eurostat.ec.europa.eu/nui/show.do?dataset=ilc_lvho07a&lang=en. Viewed 27 September 2018.

Helbrecht, Ilse / Geilenheuser, Tim (2012): Demographischer Wandel, Generationeneffekte und Wohnungsmarktentwicklung: Wohneigentum als Altersvorsorge? In: Raumforschung und Raumordnung, 70 (5), 425–436.

Hills, John / Cunliffe, Jack / Obolenskaya, Polina / Karagiannaki, Eleni (2015): Falling behind, getting ahead: the changing structure of inequality in the UK, 2007-2013. Social Policy in Cold Climate. London: LSE.

Leach, Jeremy / Broeks, Miriam / Østenvik, Kristin / Kingman, David (2016): European Intergenerational Fairness Index: A Crisis for the Young. London: Intergenerational Foundation: http://www.if.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/European-Intergenerational-Fairness-Index_Final-2016.pdf. Viewed 27 September 2018.

Lennartz, Christian / Helbrecht, Ilse (2018): The housing careers of younger adults and intergenerational support in Germany’s ‘society of renters’. In: Housing Studies, 33 (2), 317-336.

Morton, Alex (2013): Housing and Intergenerational Fairness. London: Policy Exchange.

National Housing Federation (2014): Broken Market, Broken Dreams. London: NHF.

Ronald, Richard / Lennartz, Christian (2018): Housing careers, intergenerational support and family relations. In: Housing Studies, 33 (2), 147-159.

Rugg, Julie J. / Quilgars, Deborah (2015): Young People and Housing: A Review of the Present Policy and Practice Landscape. In: Youth and Policy. Issue 114.

Shaw, Randy (2018): Generation Priced Out. Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America, Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

Shelter (2010): The Human Cost: How the Lack of Affordable Housing Impacts on All Aspects of Life. London: Shelter.

Intergenerational Justice Prize 2017/2018

***DEADLINE EXPIRED 31 JULY 2018***

The subject of this prize was:

“How attractive are political parties and trade unions to young people?”

The Winners

The jury selected five winners, with the €10,000 prize divided hierarchically:

1st Prize:

Mona Lena Krook / Mary Nugent: “Not Too Young to Run? Age Requirements and Young People in Elected Office”

2nd Prize:

Philipp Köbe: “Wie politische Organisationen für junge Erwachsene attaktiver werden können” (How can Young Adults’ Political Organisations be made more Appealing?)

Equal 3rd Prize:

Thomas Tozer: “Is there a Sound Democratic Case for Raising the Membership of Young People in Political Parties and Trade Unions through Descriptive Representation?”

Aksel Sundström / Daniel Stockemer: “Youth Representation in the European Parliament: The limited effect of political party characteristics”

5th Prize:

Emilien Paulis: “What’s Going Around? A social network explanation of youth party membership”

The winning papers will be published in two issues of the Intergenerational Justice Review (IGJR): 2-2018 und 1-2019. The first of these is now available and contains the papers of Krook and Nugent, Sundström and Stockemer, and Tozer.

The jury

Prof. Ann-Kristin Kölln (Aarhus University, Denmark), Chair, and Guest Editor of IGJR

Prof. Susan E. Scarrow (University of Houston, USA)

Prof. Matt Henn (Nottingham Trent University, UK)

Prof. Jan van Deth (University of Mannheim, Germany)

Dr Kate Dommett (University of Sheffield, UK)

Dr Craig Berry (Manchester Metropolitan University, UK)

Dr Bettina Munimus (formerly of the FRFG)

Here is the original published specification for the prize:

The Stuttgart-based Foundation for the Rights of Future Generations (FRFG) and the London-based Intergenerational Foundation (IF) jointly award the biennial Intergenerational Justice Prize, endowed with EUR 10,000 (ten thousand euros) in total prize-money, to essay-writers who address political and demographic issues pertaining to the field of intergenerational justice. The prize was initiated and is funded by the Apfelbaum Foundation.

Aim of the Competition

Through the prize, the FRFG and IF seek to promote discussion about intergenerational justice in society, and, by providing a scholarly basis to the debate, establish new perspectives for decision-makers. The invitation to enter the competition is extended especially to young academics from all disciplines.

For the 2017/2018 prize, the FRFG and IF call for papers on the following topic:

“How attractive are political parties and trade unions to young people?”

Prizes

The Intergenerational Justice Prize is endowed with EUR 10,000. The prize money will be distributed proportionally among the best submissions, which can be more or less than the top three submissions. Winning submissions will be considered for publication by the editorial team of the Intergenerational Justice Review (IGJR; www.igjr.org) for the winter issue 2018.

Closing date: DEADLINE EXTENDED TO 31 JULY 2018 (formerly 1 July 2018)

Eligibility:

- researchers from all fields of social science, especially young researchers (students, graduates, post-docs). There is no age limit. Collaborative submissions are also welcome.

Entries

- can be submitted in English or German

- should be 5,000 to 8,000 words in length (excluding figures, tables and bibliography)

Topic abstract

Political parties are intrinsically linked to the functioning of modern democracies. They provide fundamental linkage mechanisms of representation and participation that connect citizens with the state (Keman 2014; Webb 2000). Party members and affiliates, more generally, are in this respect one of the linking mechanisms that are beneficial for the effective functioning of political representation.

Members are often described as the “eyes and ears” (Kölln/Polk 2017; Kölln 2017) of parties in the electorate because of their communicative role. They bring new policy ideas to the party and communicate the party’s programme within society. In addition, members are among the primary sources of political personnel because party membership is often an informal prerequisite for acquiring political office. From this representative perspective and following the notion of “descriptive representation” (Mainsbridge 1999), members’ social makeup should ideally reflect that of the general population.

Although party members have hardly ever been entirely representative of the population in their demographic characteristics (Scarrow/Gezgor 2010), the general decline of party membership seems to affect younger generations disproportionately. They enrol less often in parties, rendering the parties’ age-profiles all too often considerably older than the broader electorate that they hope to embrace (Bruter/Harrison 2009; Scarrow/Gezgor 2010). For instance, the share of young members (under 26 years old) in German parties is at most 6.3 % (LINKE) but can also be as little as 2.2 % (CSU) (Niedermayer 2016). In contrast, around one quarter of the general population belongs to this age group. And even though the age-profile of Swedish parties is considerably better, with over 14 % of members being under 26 years old (Kölln/Polk 2017), this figure is largely driven by members of the Green Party (Miljöpartiet) in which almost 26 % are under 26 years old. In other countries, hardly any of these problems seem to exist. According to 2017 figures from the United Kingdom, the share of members aged 18-24 reflects the general population of 8.9 % quite well: group size estimates suggest that 18-24s make up 14.4 % of the Green Party, 13.2 % of the Conservative Party and 11.5 % of the Labour Party, with only the Scottish National Party and UK Independence Party (UKIP) below the 8.9 %, at 6.9 % and 6.7 % respectively (UK Party Members Project; https://esrcpartymembersproject.org).

Overall, however, the statistics suggest not only an age problem in political parties across many European democracies, but also substantial country- and party-level differences. German parties seem to be doing particularly poorly in the descriptive representation of the young, while other countries and individual parties are apparently much better in engaging younger generations.

Trade unions are facing similar problems in recruiting young members across Europe (Gumbrell-McCormick/Hyman 2013). Reasons for this pattern might be found in the dominant political issues that trade unions care about. Younger people are confronted with the rapidly changing nature of the workplace as well as the rise in temporary work and zero-hours contracts, and are probably more interested in salaries, entry requirements and work contracts, rather than in end-of-career matters such as pensions and retirement ages. The skewed age profile of trade unions could shift the discussion more towards the latter concerns, deterring younger generations and reinforcing existing age problems.

Given members’ importance and their overall age profile, it could be argued that political power or access to it is unequally distributed between the young and old. Parties and trade unions might be disproportionately representing older rather than younger generations because of their own social-demographic makeup. This could create an unjust distribution of political influence between living generations.

Scope

The Intergenerational Justice Prize 2017/18 aims to illuminate the complex relationship between young people and political parties and trade unions. It invites analyses of proposals for reform from the literature, such as an introductory stage of full membership and reforms of party conventions, participatory modes and structures.

Entries to the competition could approach the topic through a broad range of questions, including:

- Is the unequal representation of young members in and for political parties and trade unions problematic from a democratic perspective?

- What about the age structure of employers’ associations? Could the underrepresentation of younger members be viewed as a problem here as well?

- How great is the reluctance of young people to engage in and for political parties and trade unions from an internationally comparative perspective, for instance OECD-wide? What can we learn from a historically comparative perspective?

- Why do young people avoid political parties and trade unions?

- Why are some parties and trade unions better than others in engaging younger people?

- What can parties and trade unions do to attract more young members or affiliates and to retain them? What lessons can be learned from examples in which specific parties or unions have accomplished this, such as recently the British Labour Party?

- What role can the youth organisations of political parties and trade unions play in increasing the attractiveness of their mother organisations?

- Do regulations prohibit specific reform measures which could render parties and unions more attractive for young people? What role do membership fees play?

- What would be the consequences if young people permanently and irrevocably eschewed political parties?

Note that these are non-binding suggestions: participants are strongly encouraged to come up with their own research puzzles. You may adapt the title according to your chosen subject, but the paper must in essence reflect the topic. All ideas presented in the submitted papers should be innovative, creative and with a focus on civil society issues, with practical applications. The FRFG and IF particularly appreciate participants trying to explain complex ideas in as simple and accessible terms as possible. Submitted research papers may employ all possible methodological approaches.

Literature cited in the text above

Bruter, Michael / Harrison, Sarah (2009): The Future of Our Democracies: Young Party Members in Europe. Basingstoke, Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

Gumbrell-McCormick, Rebecca / Hyman, Richard (2013): Trade Unions in Western Europe: Hard Times, Hard Choices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Keman, Hans (2014): Democratic Performance of Parties and Legitimacy in Europe. In: West European Politics. Vol. 37 (2/2014), 309–330.

Kölln, Ann-Kristin (2017): Has Party Members’ Representativeness Changed Over Time? In Anderssoon, Ulrika et al. (eds.): Larmar och gör sig till. SOM-undersökningen 2016, SOM-rapport no. 70, Gothenburg: SOM-Institut, 387–400.

Kölln, Ann-Kristin / Polk, Jonathan (2017): Emancipated party members: Examining ideological incongruence within political parties. In: Party Politics, Vol. 23 (1/2017), 18–29.

Mansbridge, Jane (1999): Should Blacks Represent Blacks and Women Represent Women? A Contingent “Yes.”, The Journal of Politics, Vol. 61 (3/1999), 628–657.

Niedermayer, Oskar (2016): Parteimitglieder in Deutschland: Version 2016. Arbeitshefte aus dem Otto-Stammer-Zentrum, Nr. 26, Berlin. http://www.polsoz.fu-berlin.de/polwiss/forschung/systeme/empsoz/schriften/Arbeitshefte/

P-PM16-NEU.pdf. Viewed on 07 November 2017.

Scarrow, Susan E. / Gezgor, Burcu (2010): Declining memberships, changing members? European political party members in a new era. In: Party Politics, Vol. 16 (6/2010), 823–843.

Webb, Paul (2000): Political parties in Western Europe: linkage, legitimacy and reform. In: Representation, Vol. 37 (3–4/2000), 203–214.

Literature suggestions

Bruter, Michael / Harrison, Sarah (2009): Tomorrow’s Leaders? Understanding the Involvement of Young Party Members in Six European Democracies. In: Comparative Political Studies, Vol. 42 (10/2009), 1259–1291.

Cross, William / Young, Lisa (2008): Factors Influencing the Decision of the Young Politically Engaged to Join a Political Party: An Investigation of the Canadian Case. In: Party Politics. Vol. 14 (3/2008), 345–369.

Fitzenberger, Bernd / Kohn, Karsten / Wang, Qingwei (2011): The Erosion of Union Membership in Germany: Determinants, Densities, Decompositions. In: Journal of Population Economics, Vol. 24 (1/2011), 141–165.

Kerrissey, Jasmine / Schofer, Evan (2013): Union Membership and Political Participation in the United States. In: Social Forces. Vol. 91 (3/2013), 895–928.

Scarrow, Susan E. (2015): Beyond Party Members: Changing Approaches to Partisan Mobilization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Van Haute, Emilie / Gauja, Anika (eds.) (2015): Party Members and Activists. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Webb, Paul / Poletti, Monica / Bale, Tim (2017): So who really does the donkey work in “multi-speed membership parties” ? Comparing the election campaign activity of party members and party supporters. In: Electoral Studies, No. 46, 64–74.

Whiteley, Paul (2014): Does regulation make political parties more popular? A multi-level analysis of party support in Europe. In: International Political Science Review. Vol. 35 (3/2014), 376–399.

Here are the details of the previous prize. The deadline was 1 July 2017. The winners will be announced in December 2017.

Demography Prize 2016/17

***DEADLINE EXPIRED 31 JULY 2017***

The subject of this prize was:

“Measuring Intergenerational Justice”

The Winners

The jury selected four winners, with the €10,000 prize divided hierarchically:

1st Prize:

Jamie McQuilkin: “Doing justice to the future: a global index of intergenerational solidarity derived from national statistics”

2nd Prize:

Laurence Kotlikoff: “Measuring Intergenerational Justice”

Equal 3rd Prize:

Natalie Laub and Christian Hagist: “Pension and Intergenerational Balance – A case study of Norway, Poland and Germany using Generational Accounting”

Bernhard Hammer, Lili Vargha and Tanja Istenic: “The Dissolution of the Generational Contract in Europe”

The winning papers were published in two issues of the Intergenerational Justice Review (IGJR): 2-2017 and 1-2018.

Topic Abstract

In recent years, there has been a rising interest in measuring and comparing intergenerational justice and the well-being of young people, both across different countries (spatially) as well as over time (temporally). While the results of these indices have been found to vary in the details, they all point in a similar direction: most industrialised countries are imposing increasing burdens on younger and future generations, as is evidenced, for example, by their high sovereign debts, youth unemployment and poverty, and perennial ecological crises.

In a 2013 study published by the Bertelsmann Foundation, and led by Pieter Vanhuysse of the UN’s European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research, a total of 29 OECD states were compared on the basis of four indicators: public debt per child; the ecological footprint created by all generations currently alive; the ratio of child- to elderly-poverty; and the distribution of social spending among generations (“elderly-bias indicator of social spending”, EBiSS). These measures were then aggregated into the “Intergenerational Justice Index” – the first of its kind.

A similar attempt to capture the wellbeing of young people is the “Youthonomics Global Index”. Published in 2015 by a France-based think tank of the same name, it analyses the situation of young people in 64 Western and non-Western countries by means of no less than 59 different social, economic and political indicators.

The most recent in line is the “European Index of Intergenerational Fairness”, launched in early 2016 by the Intergenerational Foundation (IF). Designed as a quantitative measurement of how the position of young people has changed across the EU, its 13 indicators include housing costs, government debt, spending on pensions and education, participation in democracy, and access to tertiary education. The index’s findings indicate that the prospects of young people across the EU have deteriorated to a ten-year low.

Entries to the competition could approach the topic through a broad range of questions, including:

• What are the methodological pitfalls of measuring intergenerational justice, and how can they be avoided? Are the existing models internally valid, and to what extent do they allow for generalisation? What are the potential sources of selection bias and measurement error?

• Are the respective indicators by which they measure intergenerational justice sufficient and appropriate, or should they be supplemented? If so, how exactly? Are they conceptually sound and well operationalised? Do they allow for replication?

• In a cross-sectional or time-series comparison, how well do “ageing societies” such as Germany, Sweden or Finland respond to the challenges of intergenerational justice? In particular, how – if at all – do they succeed in balancing the welfare spending between the young and the old, and what measures ought they be taking in this regard?

• With regard to the country rankings, is intergenerational justice, as measured by the different indices, a function of some other set of variables – i.e., how do they correlate with alternative rankings, socio-economic or other, and what might this teach us?

• What promising policy options are there for reducing existing injustices between the young and the old? How might they be implemented?

• What measures of institutional design could be taken in order to prevent the marginalisation of young people and future generations in political decision-making? For example, should suffrage be extended or even universalised to include the currently disenfranchised, and what would be the prospective effects of such a move?

Note that these are non-binding suggestions: participants are strongly encouraged to come up with their own essay questions or research puzzles, as long as they pertain to the overall topic of this call for papers in a sufficiently clear way. Submissions are welcome from all fields of social science, including (but not limited to) political science, sociology, economics, and legal studies. Philosophers and/or ethicists are invited to contribute applied normative research.

References

Gál, Róbert Iván / Vanhuysse, Pieter / Vargha, Lili (2016). Pro-elderly welfare states within pro-child societies: Incorporating family cash and time into intergenerational transfers analysis, Hitotsubashi University Centre for Economic Institutions WPS, 17(6).

Leach, J. / Broeks, M. / Østensvik, K. S. / Kingman, D. (2016). European intergenerational fairness index: A crisis for the young. London: Intergenerational Foundation. www.if.org.uk/archives/7658/the-if-european-intergenerational-unfairness-index-2016

Tepe, Markus / Vanhuysse, Pieter (2009). “Are Aging OECD Welfare States on the Path to the Politics of Gerontocracy? Evidence from 18 Democracies, 1980-2002”, in: Journal of Public Policy, 29 (1), S. 1-28.

Tepe, Markus / Vanhuysse, Pieter (2010). “Elderly bias, new social risks and social spending: change and timing in eight programmes across four worlds of welfare, 1980-2003”, in: Journal of European Social Policy, 20(3), S. 217-243.

Vanhuysse, P. (2013). Intergenerational justice in aging societies: A cross-national comparison of 29 OECD countries. Bertelsmann-Stiftung. https://www.bertelsmann-stiftung.de/en/publications/publication/did/intergenerational-justice-in-aging-societies

Youthonomics (ed.) (2015). Youthonomics global index 2015: Putting the young at the top of the global agenda. Paris. www.youthonomics.com/youthonomics-index