Danny Dorling is the Halford Mackinder Professor of Geography of the School of Geography and the Environment of the University of Oxford, and the author of many books including All That Is Solid, Inequality and the 1%, and Injustice: why social inequality persists. In this blog, he explains how inequality between older and younger generations is bad for everyone, and why our gerontocratic status quo is fundamentally unsustainable.

Ageing society

There is a time-honoured, effective, but ultimately illogical argument made about generations. The argument goes along these lines: an ageing society doesn’t particularly need a vision of the future. It doesn’t need something better to look forward to because it contains so many very old people and they tend to live for today. They know they haven’t got long to go.

In an ageing society one political party emerges as the dominant old people’s party. That party will always present itself as holding what it thinks will be the most popular positions amongst the most elderly in society: pensioners and better-off older workers. These are its core support groups, groups that it thinks will always be growing in size.

The Gerontocracy

So often in countries with an ageing population we are told we are destined to be governed by politicians who will aim to ensure that house prices forever keep rising. We are told that the political party of the old will always try to redistribute to pensioners rather than to those who are poorer but are not pensioners; that the long-term consequences of such behaviour is not a concern to the party’s supporters because, demographically, few of this group will be around to suffer those long-term implications. This political party only pays lip service to climate change.

The party of the old does not really care if there are a lack of new homes to allow people to start new families, if the already low birth-rate continues to fall, or if the introduction of the market into British universities causes some to fail. For them it doesn’t matter if opportunities for younger Britons to work or study abroad shrink.

What does matter to them is that they ensure that the property rights of its more affluent older voters are preserved abroad over their second and holiday homes. The party of the old is less interested in emigrants, as they are potentially gone forever politically; but does care about those it calls expats.

Superficially convincing

The argument can be convincing at times and there are often signs that it is credible. The party of the old finds ways to encourage guest workers to come and carry out work on a temporary basis, hardly ever securing citizenship. Simultaneously, it encourages its older supporters to complain about immigration to distinguish itself from the alternatives.

The old people’s party encourages the young to split their political allegiances between progressive nationalist parties, greens, liberals, social democrats and as many other causes and battles as it can. It often takes part in debate simply to cause rancour and spread division. At the very same time the old people’s party works hardest of all to hide any internal dissent and to ensure that its support-base, if ever split, quickly coalesces politically.

Why is the argument illogical? Here are just a half-dozen reasons: 1) because ageing cannot continue forever, especially during a pandemic and its aftermath; 2) because the old are not a single block with a single set of interests who do not care about others ; 3) because a depleted society is immediately unable to supply enough of the health and care needs most often required by the old; 4) because the overall harm caused is much greater than any short-term gains made; 5) because all humans need a vision of the future and hope, regardless of their age; 6) because in those counties where a party of the old has emerged, society is actually far more split by income and wealth than it is between young and old.

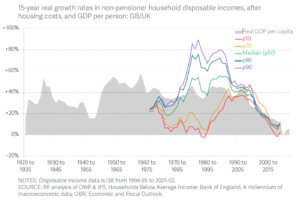

The USA and UK are now famous for their old-age political parties. However, as the Resolution Foundation demonstrated in July 2022, and illustrated with one single simple devastating graphic (shown below), the UK went from being a relatively equitable state in the 1960s – with low intergenerational inequality and high overall equality – to the most unequal large country in Europe, where over the last twenty years all non-pensioner groups have now seen any income rises end.

Source: Adam Corlett, Felicia Odamtten & Lalitha Try, The Living Standards Audit 2022, July, The Resolution Foundation, page 18.

Practically doomed

The five coloured lines in the figure above all now run in parallel and all point downwards apart from an upward blip the very latest year, the year before high inflation struck. These lines are the portents for the end of the great lie: that an ageing society will always reward the old.

The richest income group in this figure, labelled ‘p90’ because it is made up of people who are better-off than 90% of others under 65, is the group represented by the line coloured purple in the Resolution Foundation illustration. It is disproportionally made up of people in their 40s, even more in their 50s, and even more in their early 60s. This best-off group is no longer seeing its income diverge from the rest. With inflation they will soon fall.

You cannot skew towards the old for very long and get away with it. Eventually the pile of lies you have built up by promising so much to so many who need do nothing for it other than vote for you comes crashing down.

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate