The celebrations for Queen Elizabeth II’s Platinum Jubilee are taking place over the upcoming weekend. To mark the occasion, the Intergenerational Foundation’s Digital Campaigns Officer Liam Hill considers, through the lens of the intergenerational contract, how the UK has changed over the last 70 years.

It goes without saying: a lot has changed in the last 70 years. There is so much that we have grown accustomed to in 2022 that would have been beyond the wildest dreams of a person living in 1952. One constant throughout that time has been a desire for progress and advancement.

But, in some ways, it seems like that progress and advancement are stalling. In the UK, the intergenerational contract is under strain: the promise that each generation will – through technological advances and the shared proceeds of growth – be a little better off than the last seems like it might be broken for the first time in a long time. Let’s look at some of the arguments.

Earnings and costs

Let’s start with one of the simplest measures of prosperity: earnings. Members of the generation born around 1952 have been better off on average than the rest of the population for almost their whole working lives, according to the IFS.

The Intergenerational Foundation’s Packhorse Generation research shows that frozen tax brackets and an unfair student finance regime will see younger workers lose out the most in the years to come. At a time when a cost of living crisis is already biting young people the hardest, a graduate earning the median salary could see a 44% decrease in their discretionary income over the next five years, according to IF’s estimates. Meanwhile, the state pension, unlike wages, rises at least with inflation, and the value of older generations’ assets grow and grow.

Housing, housing, housing

Housing is one of the biggest strains on the intergenerational contract. The average property price in 1952 was just £2,000. In today’s money, that would be around a fifth of the figure that house prices have ballooned to instead.

As IF’s Co-Founder Shiv Malik has pointed out:

Imagine if the average house cost 56k or even 80k? Imagine how much that would change the life of young families? How much extra spending that would free up? How much extra leisure time that would create? How much more ppl would be willing to risk to start their own businesses? https://t.co/H8LWcjE0Ub

— shivmalik.eth – #dataunions (@shivmalik) May 23, 2022

House building in England peaked in 1968, a year in which 413,700 new dwellings were built. This is compared with a pre-pandemic figure of 241,000, still well off the government’s 300,000 per year target.

The UK has to build 1.2 million new homes to satisfy the demand there is, but instead (through policies like Help to Buy) the government has opted to even further boost demand. The failure to deliver enough new supply is incurring further and faster price increases.

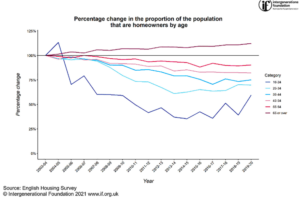

Pushing into overdrive the post-war pattern of increasing home ownership, the 1980s saw a massive programme of privatisation of council housing. In the time since, spiralling costs have seen homeownership drift from the grasp of younger generations – the only age group more likely to own their homes than the same age group was twenty years ago are those now aged 65 or above.

Concentrating wealth, stockpiling space

Around half of homes were owned, as opposed to rented, in 1970. This figure is now 7 in 10 for the population as a whole, and 85% for those born around 1952, 14% of whom also own a second home. And while this property wealth, increasingly concentrated in the hands of older generations, will reach members of younger generations eventually, it will make the UK a much more unequal society in doing so, the IFS has found.

An IF paper published last year found that older, wealthier homeowners had effectively been Stockpiling Space during the pandemic, buying houses with more rooms and with garden space. This has further exacerbated the housing crisis, pushing up prices at dramatic rates outside the UK’s big cities.

What kind of growth?

We seem to have become a society and an economy which prioritises growth in property prices over economic growth or wage growth. Policies which could drive future growth through innovation are made impossible by our restrictive planning system, NIMBYism, and some political parties’ desires to further boost the assets of their core voters.

Without building new homes, and delivering planning reform to make it happen, the UK could be stuck in this same spiral, impoverishing many younger people for the foreseeable future/on the altar of house prices.

Progress, interrupted

It hasn’t been all one way: different governments have pursued policies which have supported and protected younger people and children; but since 2010, government priorities have seemed to shift.

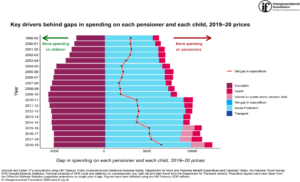

Cuts to education and the triple lock on pensions have seen the gap in per person government spending swing decisively towards pensioners.

Government spending is not the only way to judge how well each generation is faring. Our paper ‘Left Behind’ assessed the decade of change since IF’s founding (2011-21) by ten different metrics: the only metric which showed improvement for younger generations was on the UK’s level of pollution and C02 emissions, which (though lower) are still too high here and remain catastrophically high across the world.

A looming climate crisis

Which brings us to the most clear and present crisis for the intergenerational contract: the climate crisis. The coal, gas, and oil burned to fuel humanity’s progress since the industrial revolution is warming the earth, with dire consequences already affecting us all.

The climate crisis is the greatest global strain on the intergenerational contract: many of those who have experienced the undoubtedly great benefits of industrialisation and technological advancement are unlikely to see the worst of the ecological consequences of that consumption. Those with power must make every effort to reduce the catastrophic effects that climate change will have on generations yet to come.

Intergenerational solidarity

The intergenerational contract is under greater strain now than at any point since 1952, but there’s no solace in despair. Here in the UK, people of all generations have the opportunity to use their voices and votes to push for positive change.

The burdens have shifted, with children and young workers now more likely to be in poverty than pensioners, and likely to live through the worst effects of the climate crisis. But, in government and the press, attitudes and priorities do not seem to have caught up. Let’s renew the intergenerational contract and make sure the world is an even better place for the generations who get to see 2092.

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate

Photo by Hello I’m Nik on Unsplash