IF intern Hugh Nicholl investigates why the growing rhetoric of intergenerational fairness has not resulted in decisive action being taken to protect the interests of younger and future generations

The prominence of intergenerational fairness in political discourse and debate is on the up. Previously a minority concern, the notion that policy today should reflect the interests and rights of younger and future generations has, in theory, attracted a wide body of supporters across the political spectrum over the course of IF’s ten years of advocacy. Yet action on intergenerational justice remains well behind these advances in rhetoric. Why is it, then, that there is such a gap between the rhetoric and reality of action on intergenerational fairness?

Rhetoric

When IF was founded in 2011, it would have been rather surprising for the Conservative Housing Secretary to draw on the language of intergenerational justice in setting out government housing policy. Yet last month the Secretary of State, Robert Jenrick, explicitly pointed to “intergenerational fairness” as one of the tenets on which the government’s aspiration to build more homes rested.

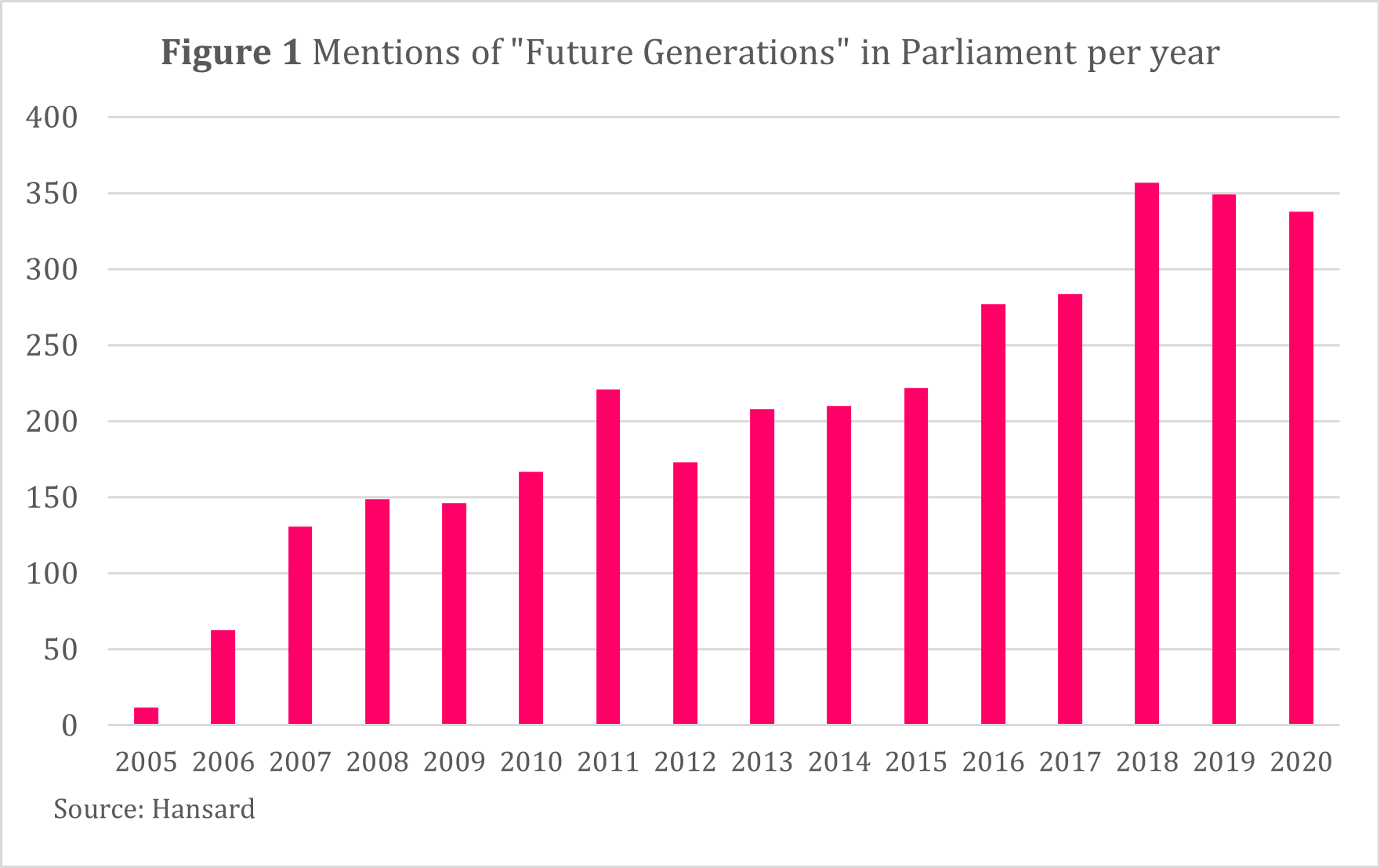

Jenrick’s use of the term illustrates the extent to which the notion of intergenerational fairness is gradually permeating throughout policy and political discourse. In fact, over the past decade and a half the belief that policy-makers today have a responsibility for future generations has become increasingly widespread. Figure 1 shows the number of references in Parliament to “future generations” each year since 2005 and demonstrates the extent to which intergenerational issues have grown in visibility.

The coronavirus pandemic has both accelerated and illustrated the extent of this shift. In October Chancellor Rishi Sunak went so far as to speak of the “sacred responsibility to future generations” that sound public finances constituted, placing the issue of intergenerational fairness at the heart of his commitment to fiscal prudence. Sunak is not the first Chancellor in recent years to use such language, though: having introduced his Spring Statement in March 2018, Philip Hammond declared himself “a great fan of the concept of intergenerational fairness” in response to a question on intergenerational injustices in the tax system.

Notably, this growing prominence of discourse on intergenerational justice has not been confined to the Right. Spurred on by the climate crisis, commitment to protecting the interests of future generations is gaining ground on the Left too. For example, in 2018 Ed Miliband – the former Labour Party leader who has recently returned to the opposition front bench as Shadow Secretary of State for Business, Energy, and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) – wrote on Twitter that “We owe it to future generations not just to have good environmental principles but to act on them.”

The link between climate change and intergenerational fairness has also been noted by Conservatives like Alok Sharma, who recently moved from BEIS to become President of the COP26 climate summit: his opening remarks at December’s pre-COP26 Australasian Emissions Reduction Summit concluded by reiterating the importance of helping “preserve our planet for future generations”.

Cross-party talk on future generations extends beyond the issue of climate change, though. Over 70 MPs have already declared their supported for the Wellbeing of Future Generations Bill, a private members’ bill sponsored by crossbench peer Lord Bird and Green MP Caroline Lucas that returns to Parliament for its second reading later this month. The Bill’s proposals include the establishment of a Commissioner for Future Generations for the United Kingdom, emulating Wales’s Future Generations Commissioner at the national level, as well as introducing a requirement for governments to consider how their legislation affects future generations through the publication of future generations impact assessments. Among the Bill’s supporters are MPs ranging from Jeremy Corbyn and Rosena Allin-Khan on the Left to influential Conservatives such as Sir Graham Brady and COVID vaccination minister Nadhim Zahawi, demonstrating the extent to which the momentum behind intergenerational fairness is building across the political spectrum.

Reality

If the rhetoric of intergenerational fairness has made significant advances, then what of the reality?

Despite the rising profile of intergenerational issues, 2020 arguably witnessed a new low for action on the matter through the dual crises of Brexit and the coronavirus. Boris Johnson’s Brexit strategy has eschewed the compromise that an intergenerationally fair settlement would have entailed – only 29% of those aged 18–24 voted to Leave, after all – and in its place sought and secured a clean break away from the EU. Many young people feel not only that their political voice has been ignored, but that their employment and educational prospects have been harmed as a result.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated further shortcomings in government action on behalf of younger and future generations. While the effects of the coronavirus have, of course, been felt across all age groups, the implications for younger people have proved noticeably absent from government policy: from unjust exam algorithms to student accommodation lockups and often ineffective government spending deferred onto future generations, the intergenerational injustices of COVID policy have been numerous.

The failure to take action on issues of intergenerational fairness has certainly not been limited to the crisis year of 2020, however. On issues such as pensions, housing, tuition fees and climate change, the reality of intergenerational fairness has too often seemed insulated from the rhetorical advances of recent years. Despite the occasional glimpses of action on intergenerational fairness – for example, the government has recently announced a long-overdue move away from RPI, a highly punitive measure of inflation for those with student debt – the overall record on delivering on intergenerational fairness has failed to match its growing visibility.

Explaining the problem

How can this mismatch between the rhetoric and reality of commitments to intergenerational fairness be explained?

There is arguably a simple answer: future generations can’t vote. While it might be excessively cynical to presume that elected politicians have no considerations beyond their short-term electoral interests, it is hardly surprising that MPs prioritise policies that favour their odds of reelection over those that reap benefits long after their political careers have come to an end.

The neglect of younger and future generations is in part an amplification of the problem of comparatively lower turnout among young voters: just as politicians refuse to tackle intergenerational injustices in areas such as the pension system due to electoral impact of older voters, so too do they neglect the interests of future generations which they have even less of an electoral incentive to serve.

IF’s latest research on Britain’s ageing political class has shed further light on the institutional barriers to intergenerationally fair policy-making, uncovering the striking extent to which young people are not represented among politicians. For example, the median age of MPs elected in the 2019 general election was 51, while the median age of members of the House of Lords is now 72, far higher than the population median of 40. If policy-making is to become more intergenerationally fair, then a political class that is less dominated by older generations would be a good place to start.

This points to the broader question of how the gap between the rhetoric and reality of intergenerationally fair policy-making can be closed. Establishing institutional mechanisms that incorporate the interests of younger and future generations into the political process would certainly help, and IF supports the efforts currently being made to implement such measures through the Future Generations Bill.

In the short term, however, securing these institutional mechanisms will likely prove an uphill struggle, especially in the absence of government support. Yet if the growing prominence of intergenerational fairness continues on its current trajectory, then there are perhaps much stronger grounds for optimism. As long as advocates for intergenerational fairness continue to make their voices heard – as is increasingly the case already – then the calls to take decisive action on the part of younger and future generations may ultimately prove irresistible. After all, even if the last decade’s significant shift in policy discourse towards intergenerational fairness has not proved a sufficient condition for a transformation in how policy-makers see their intergenerational responsibilities, it may well still constitute a necessary one.

Photo by Miguel A. Amutio on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/@amutiomi

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate