Statistical modelling shows there is a trade-off between the disadvantages of isolating the older members of society and protecting them as the most vulnerable to COVID-19. Essentially, better outcomes could result by treating the generations differently. It’s a thorny intergenerational issue, as IF Research Intern Ellie Maher explains

With increased understanding and knowledge of the coronavirus pandemic, age-segregated guidelines are subtly appearing in the government’s approach to the second wave of COVID-19 infections. Whilst Boris Johnson confirmed that “schools, colleges and universities will stay open because nothing is more important than the education, health and wellbeing of our young people”, councils tell care homes to lock down again as coronavirus cases rise.

The science says “yes”

A report by cemmap (the Centre for Microdata Methods and Practice, a joint venture of the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) and the Department of Economics at University College London), published in April 2020, presents a Multi-Risk SIR Model with optimally targeted lockdowns to predict the impact on fatalities and economic cost.

The research uses an adapted version of the SIR model which looks at the susceptible (S), infectious (I) and removed (R) populations (those in the removed category have either died or gained immunity) and the amount of contact between them in order to calculate the “rate of reproduction”, or infamous R-rate.

However, the Multi-Risk SIR model factors in variables in hospitalisation and fatality rates between groups – in particular between the “young” (aged 20–44), “middle-aged” (45–65) and “old” (65+). Assuming the only differences in interactions between the three groups come from different lockdown policies, this allows us to make predictions of fatality rates and economic costs under different lockdown measures.

Summarising these findings in a table clearly illustrates that an age-segregated lockdown is the most effective and beneficial approach.

| Type of lockdown

|

Fatalities as a percentage of the population | Economic cost as a percentage of one year’s GDP |

| Uniform lockdown with constant rate of contact between age-groups | 1.83% | 24.29% |

| Uniform lockdown with restrictions between the “old” age-group and the rest of the population | 1.34% | 17.59% |

| Uniform lockdown with an effective track and trace system | 1.28% | 16.6% |

| Age-segregated lockdown | 1.02% | 12.81% |

| Age-segregated lockdown with further restrictions between the “old” age-group and the rest of the population | 0.63% | 7.96% |

| Age-segregated lockdown with an effective track and trace system | 0.57% | 5.87% |

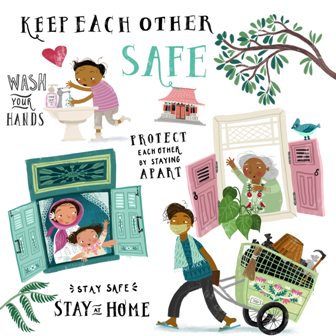

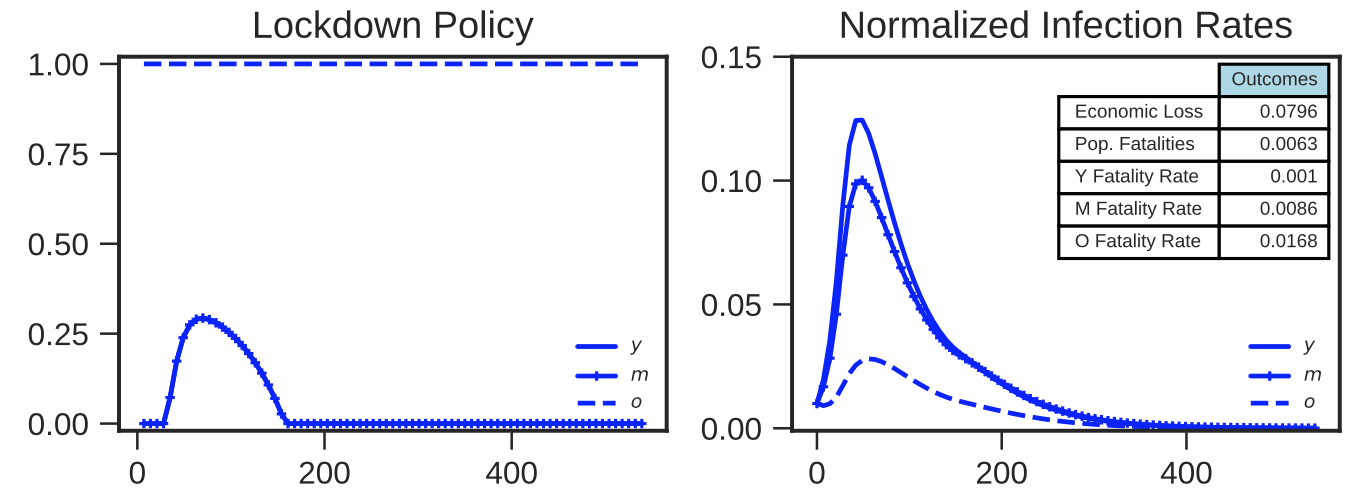

To begin with, Figure 1 shows the impacts of a uniform lockdown for all members of the population, assuming contact between population members is constant – i.e. a person in the “middle-aged” category has the same rate of contact with those in the “young” and “old” categories.

Figure 1: Projection for a uniform lockdown for all age-groups (Source: A Multi-Risk SIR Model with Optimally Targeted Lockdown Report, IFS, p.9)

(The graph on the left-hand side presents the severity of lockdown measures enforced – 0 being no restrictions and 1 being complete lockdown – against time, which is measured in days until a vaccine is distributed throughout society. The graph on the right-hand side presents infection rates against time, which is again measured in days until a vaccine is distributed. This remains consistent throughout all the graphs.)

Figure 1 shows a relatively long lockdown where restrictions remain around 0.6. We see one peak of infection rates at 6% and then a slow decline. This type of lockdown has the highest fatality rate of 1.83% and an extremely high economic cost of 24.29% of one year’s GDP.

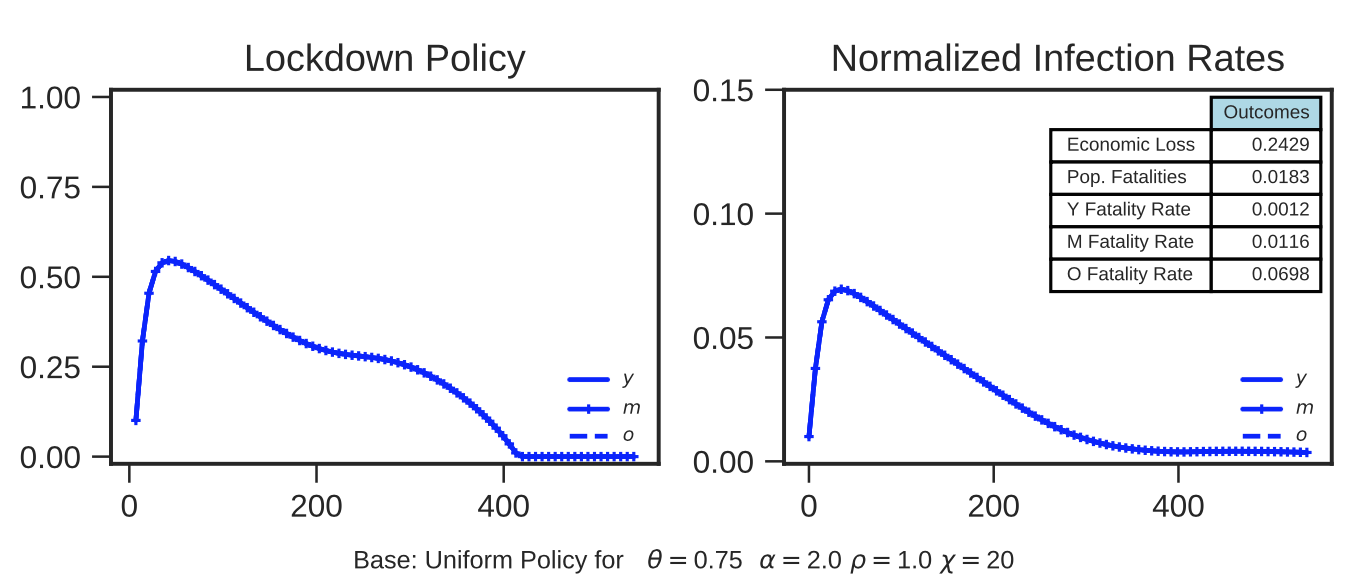

The same model but with a semi-targeted policy is shown in Figure 2. Here there is a strict lockdown for the oldest in society, with restrictions remaining constant at 1, whilst the other two groups experience a less severe and shorter lockdown. This leads to a higher peak of an 11% infection rate for the “young” and “middle-aged” categories but a shorter lockdown due to the impacts of partial herd immunity. The reason why the “old” generation experience a peak of a 4% infection rate is because the model assumes that the lockdown is not fully enforced and only abided by for 75% of the time.

Despite a much less severe lockdown for 79% of the population (the “young” and “middle-aged”), we see lower fatality rates across all age-groups, amounting to 1.02% across the whole population, and the economic cost of 12.81% of one year’s GDP – a reduction of 11.5%.

Figure 2: Projection for a targeted lockdown for different age-groups (Source: A Multi-Risk SIR Model with Optimally Targeted Lockdown Report, IFS, p.20)

For the above two models, it is assumed that there is a constant rate of infection between and within age-groups. However, this can be modified to gain a more accurate prediction for targeted policies.

A new intervention, such as restricted visiting to care homes, could dramatically change the rate of contact between the “old” age-group and the rest of the population. Assuming these changes halve the frequency of interaction between these groups, under a uniform lockdown the model finds that fatality decreases to 1.34% and keeps the economic cost to 17.6% of one year’s GDP – as Figure 3 shows.

Figure 3: Projection for a uniform lockdown where the rate of contact between the “old” age-group and the rest of the population is halved (Source: A Multi-Risk SIR Model with Optimally Targeted Lockdown Report, IFS, p.24)

This restriction can then be combined with a targeted lockdown to further reduce fatality rates – to 0.63% – and mitigate economic costs to 7.96% of one year’s GDP.

Figure 4: Projection for a targeted lockdown where the rate of contact between the “old” age-group and the rest of the population is halved (Source: The Institute of Fiscal Studies A Multi-Risk SIR Model with Optimally Targeted Lockdown Report, IFS, p.24)

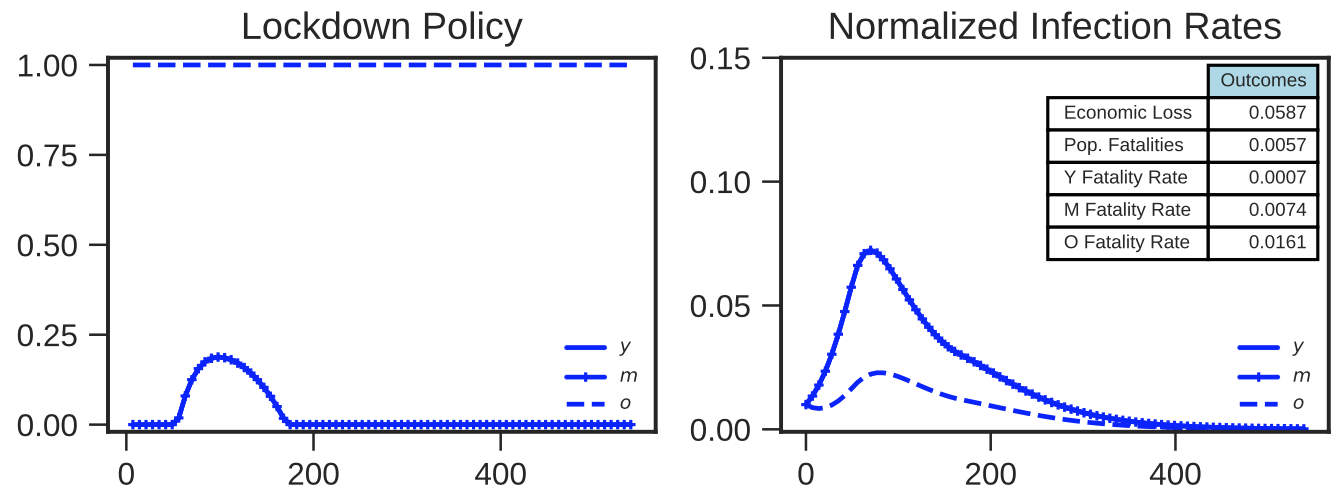

Instead of restrictions reducing contact between the “old” age-group and the rest of the populations, introducing an effective track and trace system predicts fatalities would reduce to 0.57%, and economic cost to 5.87% of one year’s GDP, as Figure 5 shows.

Figure 5: Projection for a targeted lockdown where the probability an infected individual is identified and isolated is 0.4 due to a track and trace system (Source: The Institute of Fiscal Studies A Multi-Risk SIR Model with Optimally Targeted Lockdown Report, IFS, p.30)

This projection assumes that the probability that an infected individual is identified and isolated is 0.4 and the lockdown for the “young” and “middle-aged” is much less strict – at around 0.2 – compared to that applied to the “old” population who are in complete lockdown. We see a relatively low infection rate amongst the “young” and “middle-aged” in comparison to Figure 2, and a much shorter lockdown for these age categories. As well, maintaining these conditions but changing to a uniform lockdown instead of targeted lockdown increases fatalities to 1.28%, and economic cost to 16.6% of one year’s GDP, illustrating again that a targeted lockdown is the most effective and beneficial proposal.

This scenario becomes more successful as the probability of an infected individual being identified and isolated increases; this could be undermined where the effectiveness of the government’s track and trace system remains questionable.

Not so quick

Although this research points to a clear proposal, mathematical models make a number of assumptions. For example, the Multi-Risk SIR model treats every member of each age-category as homogeneous, which is not the case. We know that age is not the only factor in determining your risk to coronavirus: underlying health conditions also play a pivotal role, meaning the model would need to be developed further to factor in subgroups within the age-categories.

As well, some may feel an age-segregated lockdown is deeply unfair on the older generation. Age UK have expressed this opinion, especially concerning the impacts on mental health if older people are kept apart from families, friends and the wider community for a prolonged period of time.

However, the younger generation are having to cope with severe changes to their education, are facing mass unemployment, have graduated into what is being forecast to be the worst recession in 300 years, and will carry the weight of the government debt – predicted to be between £263bn and £391bn – for a large majority of their lives. Therefore it could be argued that the mental health of the young is a greater cause of concern as we approach the second wave of infections.

An age-segregated lockdown may also increase hostility between age-groups. This is a legitimate concern, but an age-segregated lockdown does not necessarily undermine the idea of a collective response to the pandemic, given that the young are essentially protecting the older generation – as Secretary of State for Health and Social Care Matt Hancock warned: “Don’t kill your gran by catching coronavirus and then passing it on.”

Weighing it up on the scales

A balance is needed between public health and the UK’s economic recovery, which an age-segregated lockdown could underpin, together with an effective track and trace system. Although this would limit the freedom of the oldest generation and could appear ageist, it may be the only way to provide some form of standard of living for the younger generations whilst protecting the lives of those most vulnerable.

Image created by Asa Gilland. Submitted for United Nations Global Call Out To Creatives – help stop the spread of COVID-19. Courtesy of Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/photos/KSUv52EZgGg

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate