In the 2019 election in Australia, the welfare of future generations was the focus of a raft of policy proposals – and from an intergenerational point of view the wrong side won. This might mark a regrettable setback for intergenerational politics as a whole. Report by Danielle Wood (Budget Policy Program Director) and Owain Emslie (Associate) at the Grattan Institute in Melbourne.

The 2019 Australian election might have been the country’s first fought on generational lines. The left-of-centre Labor Party pitched a fair go for young people, and promoted tax policies such as winding back generous tax credits for retirees and a reduction in tax concessions for housing investors to help first home buyers. The right-of-centre Coalition, declared it an “age war” , stoking retiree anger directed at Labor’s policies, and pledging to protect retirees’ wealth.

When the Coalition achieved a surprise victory, many commentators were quick to point the finger at Labor’s bold reform package. There is now a real concern that intergenerational equity could be pushed off the Australian policy agenda altogether, as would-be governments fear a backlash from an ageing voter base. This would be a disappointing stance. Young Australians face very real concerns about housing affordability, stagnating wealth and incomes and future budget pressures.

Young Australians: stagnating wealth and spending power

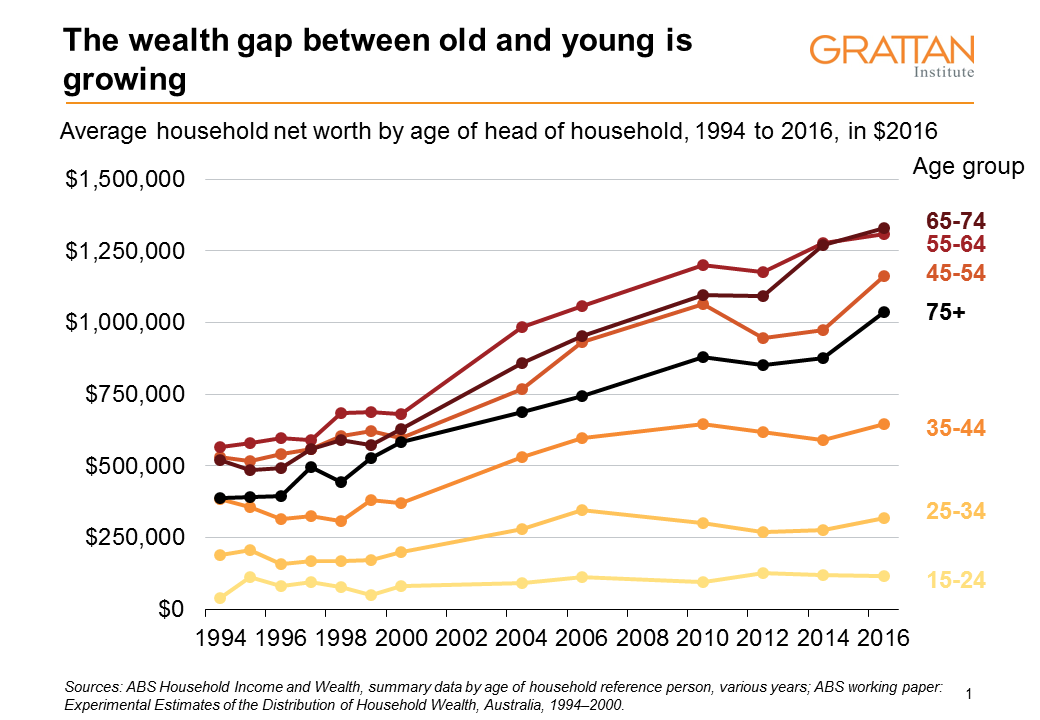

The wealth of households under 35 has barely moved since 2004 (Chart 1, below). And poorer younger Australians have gone backwards. Younger Australians are much less likely to own a home than their parents were at the same age. Home ownership rates for 30-year-olds fell from 65% in 1981 to 45% in 2016. In contrast, older households’ wealth has grown by more than 50% over the same period because of the housing boom and growth in superannuation assets.

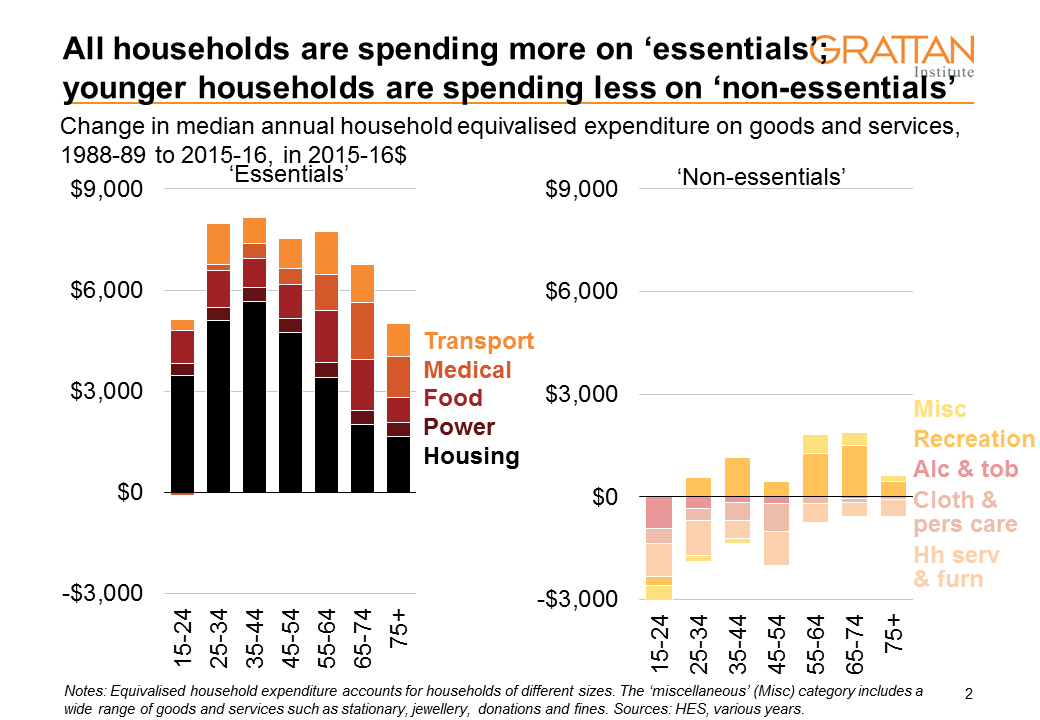

There is no evidence that young Australians’ spending habits are to blame for their stagnating wealth – this is not a problem caused by smashed avocado brunches.

In 2015–16, spending by households headed by someone aged 15–34 was only 10–30% higher than in 1988–89. By contrast, spending by households headed by someone aged 55 or older was 50–80% higher.

All the increase in spending for younger households was driven by increases in spending on essential items, particularly housing. Young people’s spending on non-essential items such as recreation has declined over the last quarter of a century (Chart 2, below).

The squeeze on the living standards of the young has been driven by recent wage stagnation and rising underemployment. Since 2008, the income of younger households has stalled, or gone backwards. Incomes for households headed by someone over 55 have continued to rise, somewhat cushioned from low wages growth by rising workforce participation (particularly amongst older women) and other income streams.

While incomes for households headed by someone under 45 are still substantially ahead of where they were in the 1980s, some of the gains have been eliminated by recent declines.

It is not yet obvious that Australians born in the 1990s will leave young adulthood with higher incomes than those born ten years earlier had at the same age. Indeed, if low wages growth and fewer working hours is the “new normal”, the well-established pattern of generation-on-generation progress in incomes will be under threat.

The ageing population

As well as possibly having less, young Australians face looming budget pressures.

Partly this is because of demographic change. Longer life expectancy, as well as the supersize Baby Boomer cohort reaching retirement age, have meant the number of working-age Australians for every person over 65 fell from 7.4 in the mid-1970s to 4.4 in 2015, and is projected to fall further to 3.2 by 2055.

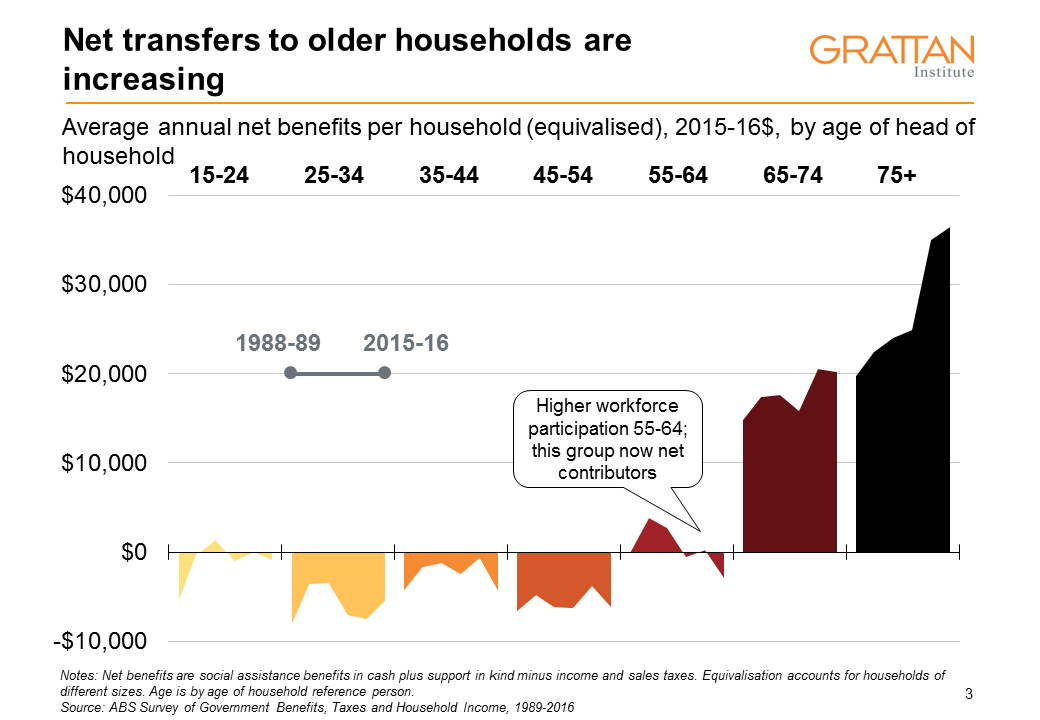

But a series of policy decisions have made things worse by substantially increasing the size of the average transfers to older households – expanding their good fortune at the expense of subsequent generations (Chart 3).

Generous tax concessions – including tax-free superannuation and special tax offsets – have been big contributors to growing transfers. The share of households over 65 paying tax has halved over the past two decades. And average income tax paid has barely changed despite strong growth in incomes and wealth.

The upshot is that working-age Australians now and in the future are underwriting the living standards of older Australians to a much greater extent than the Baby Boomers did for their forebears.

People born in the late 1940s, at the beginning of the Baby Boom generation, reached their peak contribution to the tax system in their early forties – and at that point they were contributing an average of $3,200 a year to support older generations in retirement. An average 40-year-old today, born at the tail end of Generation X, is paying $7,300 a year.

Under current policy settings, the child of today’s 40-year-old will need to pay around $11,400 a year by the time they reach 40 just to sustain current levels of benefits.

Solutions

There are sensible policy changes that could help boost the economic fortunes of Australia’s young. Boosting economic growth and improving the structural budget position are wins for all, but especially for the young. Changes to planning rules to encourage higher-density living in established city suburbs would make housing more affordable. And a fair go for younger people means reducing or eliminating age-based tax breaks that are pushing a growing tax burden onto working Australians.

Older Australians are not selfish – they make large contributions to subsequent generations, through unpaid childcare, gifts and community work. They care about the welfare of their own children and grandchildren, as well as the world they are leaving for future generations. Even in the recent Australian election, there is little evidence that wealthy retirees voted largely in self-interest.

However, there is a risk that our political leaders will think the safest option is to avoid changes that will dent the fortunes of older Australians. To do so would be to give retirees too little credit for altruism – and risk selling all our futures short.