The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has recently produced some research which estimated the likelihood of different categories of jobs being automated over the coming years. Worryingly, this found that jobs which are disproportionately done by younger workers are some of the ones which are at the greatest risk of being automated. David Kingman ponders what this could mean for young people and intergenerational fairness

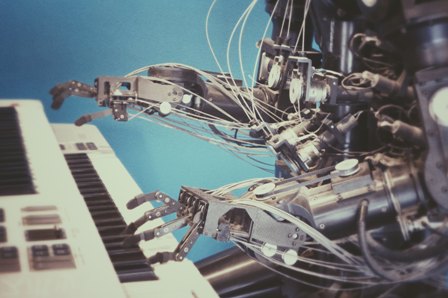

The spectre of jobs being replaced by machine is a hot topic at the moment, despite the fact that the UK is currently enjoying record employment. Although technological innovations rendering obsolete jobs which used to be commonplace is nothing new – it’s why you can no longer find much work as a knocker upper, for example, or as an iceman – there is now a high degree of anxiety that the extremely rapid pace of technological change which the world is currently witnessing could result in the mass replacement of human workers with automated processes in fields where this has never previously been possible.

Over the past few years, a burgeoning literature of economics research papers has been published which attempts to forecast how many jobs could be automated in the near future (although, as I will explain, several of them reach wildly different conclusions). Concerns have been expressed that, if taken to its logical conclusion, the process of automation could produce a Blade Runner-like dystopia, in which a privileged elite – which possess the skills and resources to interact with the incredibly powerful machines society has come to rely on – lives in luxury while the unemployed masses are forced to subsist on the margins of society.

Perhaps on a more plausible note, given that most advanced economies have seen a dramatic increase in economic inequality since the 1980s, it is sensible to be concerned that a shift towards the increasing automation of more routine and manual jobs could exacerbate these inequalities further.

This is also likely to have a bearing on intergenerational inequality, because if – as IF has often argued – the declining living standards of today’s young adults are likely to make inheriting wealth more important in determining somebody’s overall level of economic wellbeing, then automation could further advantage the young adults who come from more privileged backgrounds because they are likely to be equipped with the necessary skills to work with the machines instead of being replaced by them.

In a very interesting new piece of research, the ONS has attempted to estimate the likelihood that different occupations which exist today could be automated in the relatively near future. Some of the results are potentially quite concerning, because they seem to suggest that it is disproportionately jobs done by younger workers that face the highest risk of automation.

How many jobs?

The ONS researchers drew in part on the methodology of a famous study which appeared in 2013 that was designed by a pair of American academics called Carl Frey and Michael Osborne, which estimated that 47% of all US jobs were at high risk of being automated within the next 10 to 20 years; when that methodology was transferred to the UK it produced an estimate that 35% of jobs could be automated over the same time frame.

Returning to the point about inequality, they also found that there was a strong inverse relationship between the wages and qualifications of US workers and the likelihood of their jobs being automated, i.e. the lowest paid and least well-qualified Americans were the ones at the greatest risk, because they tended to do the most menial and routine occupations.

However, their methodology was challenged by a follow-up study from the OECD, whose authors argued that Frey and Osborne had arrived at such an alarmingly high estimate because they hadn’t looked at the individual tasks which make up a job.

The authors of this paper argued that instead of it being the case that some jobs are capable of being fully automated while others are not, it’s more accurate to think of all jobs as consisting of a wide array of different tasks, some of which are more susceptible to automation than others. Therefore, a job is only at risk of being fully replaced by automation if a very large proportion of the “bundle of tasks” which it encompasses can all be automated. Using a different dataset which attempted to divide different jobs into their constituent tasks, this approach produced a much lower estimate of the total share of jobs which might be automated; they estimated that across all 21 OECD countries, just 9% of jobs are at risk of disappearing completely.

An example of the difference between the two approaches is the implications they would have for the future demand for shop assistants. Frey and Osborne’s approach suggests that virtually all shop assistants could be replaced one day by technology because their jobs mainly revolve around routine tasks which it should be possible to automate (such as swiping items of shopping across a barcode scanner).

However, the OECD study approach would suggest that when you break being a shop assistant down into a bundle of tasks, while many of them could be automated a big part of the job is also interacting with customers, which probably can’t be (think of modern supermarkets, which still need to employ a certain number of shop assistants to help customers use self-service tills). Therefore, this would suggest that a smaller proportion of shop assistants are likely to disappear than Frey and Osborne estimated.

How many UK jobs are at risk?

The ONS used an adapted version of the OECD methodology to create a regression model which estimated the probability of different jobs being automated in the UK, and then used data from the Annual Population Survey to estimate how many people actually do these kinds of jobs.

Their headline finding was that 7.4% of all UK jobs were at “high risk” of automation (meaning the likelihood of them being automated was predicted to be greater than 70%); although this is a relatively small proportion of the total, it would still amount to 1.5 million UK jobs.

In line with most other attempts at forecasting the future of job automation, the jobs at highest risk of automation are predominantly manual and routine jobs done by low-skilled workers (those whose highest qualifications are A-levels or below), including shelf-stackers, machinists, dry cleaners, van drivers and cashiers.

By contrast, it is the jobs which involve either advanced technical skills, such as research and development or computer programming, or excellent people skills and decision-making abilities, such as senior management, that are at the lowest risk.

More significantly from an intergenerational fairness point of view, the jobs which are at the highest risk of automation are disproportionately done by younger people: over 45% of the high-risk jobs are done by people between the ages of 20 and 30 years.

The ONS argued that this is because younger workers are more likely to hold low-skilled jobs temporarily, for example while they are studying, before moving on into higher-skilled ones. However, it does raise a couple of important questions. Firstly, what kind of low-skilled jobs will be available in the future for young adults who want to get their foot on the first rung of the labour market, if fewer of the traditional routes into paid employment no longer exist? And secondly, what about the young adults who remain stuck in low-paid employment – are they doomed to a future in which their working lives will be increasingly precarious?

Obviously, prognosticating about the future direction of technological trends often proves to be a fool’s errand. The ONS itself observed that employment is currently increasing in 12 of the 20 occupations which they thought were at the greatest risk of being automated.

However, the concerning implication which many of these studies raise is that over the long term, young people who don’t manage to move on into higher-skilled jobs are in much more danger of being replaced by machines than those who do. Given that older generations are less likely to be affected, the risk of greater intergenerational inequality looms.

Photo by Franck V on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/@franckinjapan

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in our work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate