With the government seemingly committed to increasing participation in higher education, IF summer Intern, Rohin Burney O’Dowd, looks to Germany for answers.

Policies shifting the burden of tuition and living costs from taxpayers to students in England has been justified on the grounds of the “basic unfairness (of) asking taxpayers to fund … people who are likely to earn a lot more than them”. Regardless of the size (and even existence) of the graduate premium, the answer isn’t to level down the earnings of the university-educated, but to level up opportunities for those who don’t attend by providing high quality vocational alternatives.

Looking back, and beyond the horizon

There is much to admire in the ethos and low costs of the 1960s UK higher education system, but to demand a return to this golden age is to look back with rose-tinted glasses — it was also a time of inaccessibility and socio-economic rigidity in universities. Though students received a modern-day equivalent of £6,000 annual grants and were charged no tuition fees, just 5% attended university, and of those who did over 40% came from private schools. Nonetheless, if viable, surely the ideal policy would be to marry the fees for students past with the high participation and social plurality of students present? In search of this, we ought to turn our gaze not backwards but outwards and learn lessons from German vocational education.

University funding and flawed logic

Like the UK, Germany is one of the world’s largest economies, is politically centre-right, and needs highly skilled, young workers due to its ageing population. But while English fees are now the highest in Europe, German university education is free. It could be argued that this is a matter of economic necessity, given that just three in ten young Germans, compared to nearly half of young Britons, attend university. Having a highly educated population is without doubt a virtue but burying the young under a mountain of debt is equally a vice.

Our government claims to be committed to three connected principles: a high participation rate is desirable; it is wrong to ask taxpayers to fund the education of those who will earn far more than them; therefore the UK higher education system is only sustainable and fair when large contributions are made by those who attend.

But the last principle does not follow from the first two. If the graduate premium — the difference between the life-time earnings of a university graduate and non-graduate — is truly as high as Minister for Universities Jo Johnson claims it to be, then the government’s focus should be upon improving the opportunities available to those who do not attend university, rather than placing an ever-growing tax on learning upon those who do.

Germany and UK compared: vocational training, and lack thereof

The opportunities we provide for non-graduates are pitiful. At the height of the Great Recession, unemployment reached 20% among 18–24 year olds and 40% among 16–17 year olds. According to a 2015 OECD report, the skill-level of Britain’s youth is in the bottom quartile of member nations. The Jilted Generation asserts that: the number of apprenticeships in Britain has fallen by a quarter since the 1960s; Labour’s New Deal for Young People saw two thirds of participants fail to hold down employment for thirteen weeks; and under the Conservatives’ Mandatory Work Activity, young people received letters threatening their benefits if they did not volunteer. If the government’s concern is fairness for non-graduates, it has a funny way of showing it

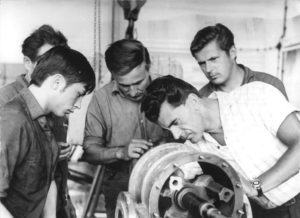

Is it possible that Germany’s famous efficiency is not a gift from god but a product of policy? Germany’s Dual Education model provides vocational schooling for students in 356 practical professions as a genuine alternative to full-time university education. Students are paid, and receive on-the-job training; combining learning in private corporations and vocational colleges. There are nationally standardised assessments after two to four years and students are certified by the Chamber of Commerce. Consequently, the German unemployment rate declined during the recession, and not simply by masking figures with supermarket shelf-stackers; 60% of the German youth are apprentices, many on highly respected career paths, learning useful skills, making contacts and absorbing the culture of the companies they work with. There is a difference in perception too: the German non-graduate is not an “at risk youth”; nor are the apprenticeships a matter of “corporate social responsibility”; the Dual Education system works because governments and businesses alike recognise that they need “skilled, thoughtful, self-reliant employees” who can “solve problems”.

Lessons in practical matters from Europe

This is not to say that the reform of vocational educational has an overnight fix; nor that we can replicate the German model which is imbedded in a different cultural and structural context. But if the government is genuinely concerned with fairness for non-graduates and sustainable funding for higher education, the answer is not to place students in £50,000 of debt, or to insult those who don’t attend university with menial, low (or no) pay jobs. Instead, we should swallow our newly emboldened national pride and follow the Germans.