The pension system in the Netherlands is often cited as one of the best in the world. This is no longer the case, and that has serious intergenerational implications, according to the Dutch pensions campaigner and author Martin Pikaart

The issue of intergenerational fairness has recently turned into a politically relevant one in the Netherlands – just as it has in the UK. This is not surprising, since many of the main driving factors behind this issue are not restricted to the UK. Some of these main factors are: an ever growing life expectancy coupled with a decreasing birth rate, global climate change, and the impact of technology on virtually all aspects of life.

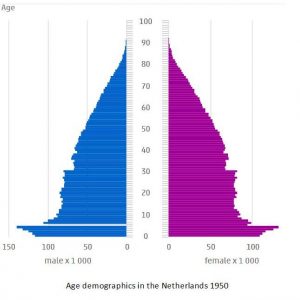

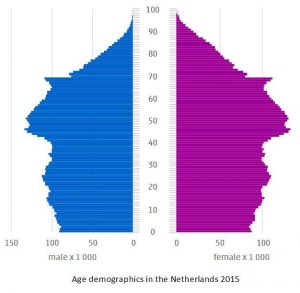

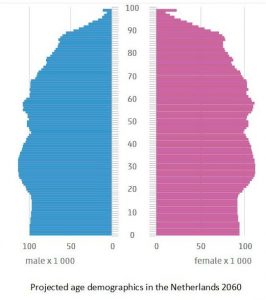

Since we are discussing generations here, the typical time scales we take into account are decades. The demographic pyramid of 1950 has grown slowly but surely into a demographic pagoda.

Let’s take a look at the demographics and the retirement situation in the Netherlands.

The state pension: pay-as-you-go

The Dutch state pension is a pay-as-you-go system that grants a fixed amount to every Dutch citizen who has reached legal retirement age. Legal retirement age was 65 from the introduction of the state pension in 1957 until 2012. Starting from 2013 the legal retirement age has been gradually increasing: it will be 67 in 2021, and starting from 2022 it will be coupled to life expectancy, leading to a retirement age of 71.5 for those born in 1988, according to the Ministry of Social Affairs. The age of 71.5 is already out-of-date, since life expectancy has been growing ever since; younger generations must probably work until they are 72 or 73 at least.

A glance at the demographics charts reveals the ever-increasing so-called grey pressure, the ratio of the working population to those aged 65+. This grey pressure will have changed from 7:1 in 1950 to 5:2 in 2050. The pay-as-you-go state pension of course reflects this rising pressure in either higher premiums or lower allowances or a combination of both.

Warnings by economists based on demographic prognoses have been voiced since the 1980s in articles such as “The future of the state pension: doubling the premiums or halving the allowances?”* However, these warnings were disregarded, as is often the case when welfare is growing.

The pension funds: defined benefit based on average pay with inflation compensation

About 90% of Dutch employees participate in one or more of the approximately 250 pension funds. These funds were founded and are run by organisations of employers and employees. For a short animation of how the Dutch pension system works, click on the video link below.

Most employees participate in mandatory sector-wide funds. Almost all of these offer a defined benefit pension based on approximately 70% of the average pay together with inflation compensation.

The nature of this promise – and especially the promise of inflation compensation – is the subject of a lot of controversy. Inflation compensation is nowadays always conditional, that is to say dependent on the coverage ratio of the fund.

In the majority of the funds, pensions were based on final salary until around 2002, after which they were trimmed back to average pay with the explicit guarantee of equivalence. This equivalence meant that although one could miss the compensation in a given year, that shortage would be compensated for by means of additional compensation a year or two later, the outcome being that, compared to a pension based on final salary, one had only been disadvantaged during one or two years.

In reality most funds had 100% inflation compensation till 2008, but nearly 0% compensation since then. Furthermore, pension funds have put a lot of effort into framing the inflation compensation promise in an entirely different manner: namely as profit-sharing. If the funds make extra profits, participants may get inflation compensation within this framework, but not otherwise.

The intergenerational unfairness in the Dutch pension system

Not only the first pillar but also the second pillar, consisting of those 250 pension funds – with a collective capital of 1,300 billion Euros – incorporates several pay-as-you-go-like mechanisms. The average ratio of assets over liabilities varies on a daily basis and has recently lain between 90 and 100%, where some 125% is needed to uphold the promises including inflation compensation.

About a decade ago, the average age at which workers retired was less than 60, due to the generous fiscal benefits for early retirement. Replacement rates usually stood at around 80% of the last-earned wage at the introduction of these plans in the 1980s. In 2006 these fiscal benefits for early retirement were abolished, with a transitional provision that let baby-boomers add their early retirement benefits to their pensions (starting at age 65).

In the meantime, future retirement arrangements have been cut, first to 70% of the last earned wage, and subsequently to 70% of the average earned wage. Simultaneously the legal retirement age is increasing, as described above. The actual retirement age is lagging behind somewhat; nevertheless it shows a clear rise to about 63. At the same time the pension premiums have risen significantly compared to those of the 1980s. If premiums stay as they are now, present-day participants will end up paying some to 50% more in premiums compared to those recently retired, over their working life.

The whole situation gives rise to an extremely skewed distribution of welfare over the generations. Younger generations have the outlook of a working career that ends some 12 years later, thus paying premiums for a much longer period and profiting from pensions for a shorter period than their baby-boom colleagues. Furthermore, the premiums are much higher now and the benefits have been severely cut.

In a modest attempt to quantify globally the differences in costs versus benefits of older and younger generations, I found that the benefits-minus-costs account for a baby-boomer on average is about 11 years’ of pay more beneficial than for someone born in the 1980s.**

Political outlook

There is broad consensus nowadays that the Dutch pension system is not as durable as it has long been thought to be. Ministry and social partners have put a decade’s efforts into exploring a new system. Given the situation the system finds itself in, there is a lot a pain to be divided. Mental pain mostly, as the promises were so luxurious that even 90% of the non-inflation-compensated promise would in many cases still provide a decent living. However, pensions are emotional, as anyone who is active in this field may affirm. It takes courage to tell pension participants – and especially retirees – the truth, but it only takes technical discussions to postpone painful decisions and thereby to enlarge the unfairness between generations.

Notwithstanding the already obviously skewed division of the benefits of our pension system, the recently founded 50+ Party is doing well in the polls for next year’s elections, indicating around 10 seats in the House of Representatives, and the PVV, usually the largest in the polls with around 30 seats, has a programme which also gives high priority to care for the elderly.

As a last remark, these parties still seem to be executing the preamble of the Labour Foundation, dating back to 1945, where unions of employers and employees make a joint call to the country with a ten-point plan to pull the Netherlands out of the ruins that the Second World War had brought them. Nine out of these ten have been abandoned as being no longer relevant. The eighth, however, “direct improvement of the allowances to the elderly”, although at least as irrelevant as the others nowadays, is still being pursued by many political parties, pension funds and other welfare institutions.

Martin Pikaart is the author of De Pensioen Mythe (see www.pensioenmythe.nl), as well as one of the founders of a new and innovative trade union AVV (www.avv.nu), which aims to change the way employers and employees think about pensions.

ENDNOTES

* Bosch, F.A.J. van den and Eekelen, P.J.C. van and Petersen, C. (1983). De toekomst van de AOW: verdubbeling van de premies of halvering van de uitkeringen? Economisch-Statistische Berichten, 68 (3431). pp. 1052-1058. ISSN 0013-0583.

** Pikaart, Martin. Lusten en lasten van de generaties in het pensioenstelsel, De Actuaris, maart 2013.