The COVID-19 lockdown is emphasising inequalities in financial resilience between the generations. They existed already, says David Kingman, but there’s a real danger the lockdown could make them worse

It’s unsurprising that many people’s finances are taking a few blows while the UK is in lockdown to try to prevent the spread of COVID-19. Although the government has done its best to try to minimise the economic impacts that the lockdown is having on ordinary households, the unprecedented level of economic disruption that the UK is going through is bound to negatively affect people who aren’t working and don’t have enough money in the bank to maintain their living standards while they wait for the lockdown to end.

Of course, different households came into the lockdown with very different levels of financial resilience to begin with, and there are also significant divides between social groups in their risk of becoming unemployed and needing to draw on their pre-existing resources in order to survive financially.

As you might expect, one of the starkest divides in financial resilience is between households in different age groups: the young are much more likely to be in a financially precarious position than the old.

This article will look at what we know about different households’ level of financial preparedness for this crisis, and how it might be affecting their finances now that everything has changed.

What is financial resilience?

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) has defined financial resilience as “the ability to cope financially when faced with a sudden fall in income or unavoidable rise in expenditure”. A “sudden fall in income” is sometimes referred to as an “income shock”, and that is likely to be the main problem which households in the UK are currently dealing with, as – while the country is in lockdown – many people are unable to earn an income in the way that they normally would.

Measuring financial resilience in a robust manner is quite difficult, because you need to understand the options which are available to households when they suffer an income shock, and you need to have some kind of model of how they might adjust their normal behaviour in response to one.

In theory, a household can respond to an income shock in several different ways. Households which have accumulated a pool of liquid assets (such as money held in cash savings accounts, or invested in a portfolio of shares) can start spending some of that money to help them maintain their usual living standards. They can achieve the same effect by resorting to borrowing (although this is riskier and more expensive). Alternatively or additionally, there might be government benefits which are available for them to claim, or they can try to reduce their expenditure temporarily.

In essence, having money in the bank which you can draw down and start spending is the option which makes it easiest to maintain your current standard of living during an income shock, so households which have a bigger pool of liquid assets to call on are considered to be more financially resilient.

Are young people less financially resilient?

The ONS recently released a new piece of research which analysed how financial resilience varies between different groups within the UK population.

Rather than attempting to model how households might either access credit or reduce their outgoings in response to an income shock, the ONS researchers simply looked at whether a household had enough money saved in liquid assets to be able maintain its current level of expenditure each month if its regular monthly income were to fall by either 25%, 50% or 75% for three months.

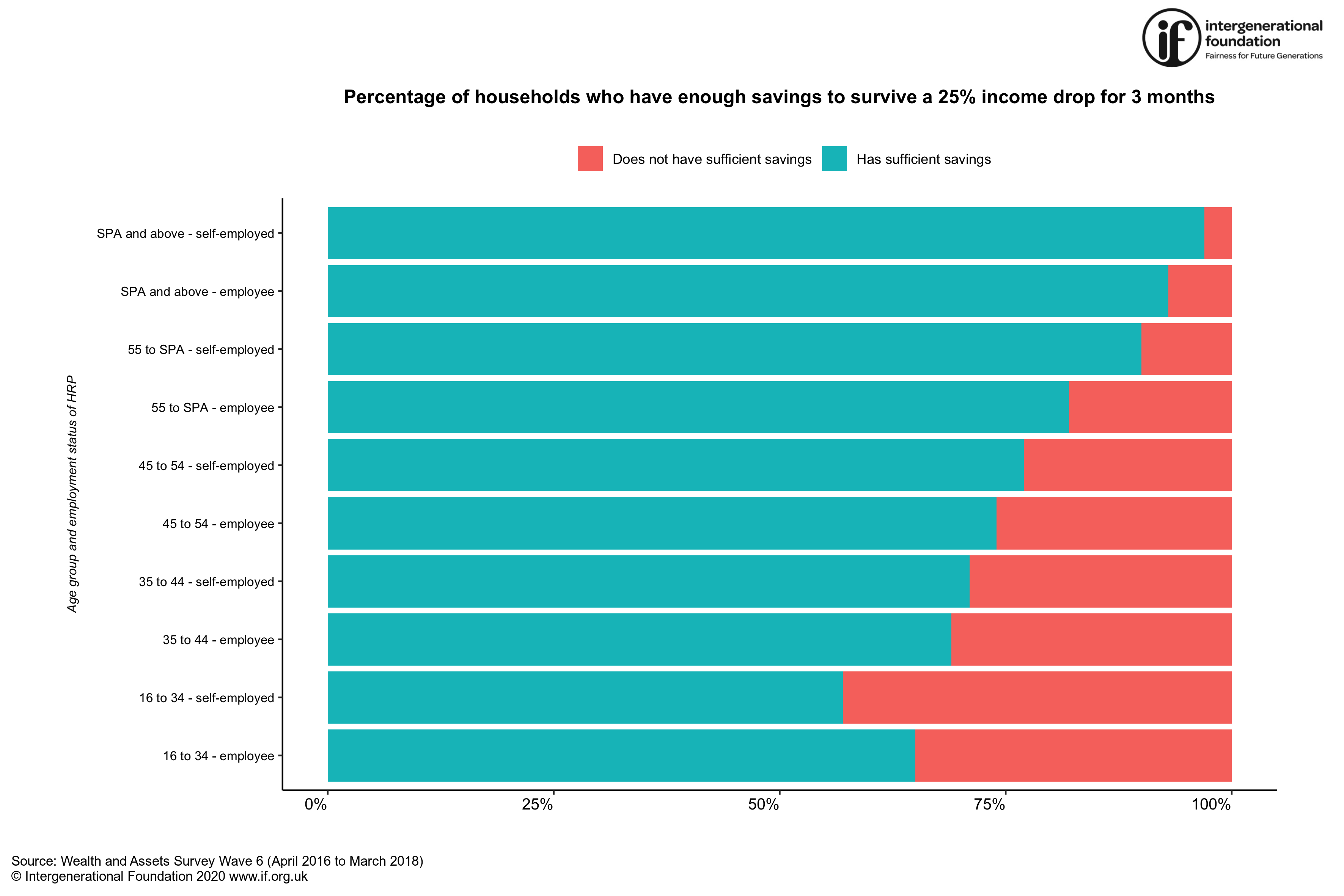

Their results showed that there were significant inequalities in levels of financial resilience across the population before this crisis struck, which were especially marked when comparing the financial resilience of different age groups (Fig.1). This is in line with what you would naturally expect to be the case, because older households tend to earn more than younger ones (up to their 40s and 50s), and they’ve had more years in which their wealth has been able to accumulate interest.

Fig.1

If we look at the data which the ONS produced on how different households would be affected by a 25% fall in income, it suggests that the youngest households (those where the Household Reference Person (HRP) was aged 16–34) would be the least likely to have enough liquid assets to maintain their previous level of expenditure.

Within this age group, 35% of all households where the HRP was an employee wouldn’t have enough liquid assets to maintain their previous standard of living (just over 1 million households) and neither would 43% of those where the HRP was self-employed (just under 135,000 households).

The risk of being in this position clearly declines with age, and among households where the HRP was above State Pension Age (SPA) the equivalent figures were just 7% and 3% respectively (although these figures include only the relatively small number of households where the HRP is above State Pension Age and is still working; the ONS didn’t include fully retired households in this analysis, presumably because they aren’t vulnerable to suffering labour market-induced income shocks).

What does this mean for COVID-19?

Obviously, these data were collected quite some time before the present crisis began, but they do paint a picture of how financial resilience varies across the population and between different age groups.

Interpreting how these inequalities might affect people’s living standards during the COVID-19 crisis is tricky because the crisis is clearly affecting different people’s incomes to different extents.

We know that younger workers disproportionately work in sectors which have been hardest hit by the COVID-19 crisis, such as retail. However, at least in theory, the vast majority of young workers should only have to grapple with a 20% income shock at most (lower than any of those modelled by the ONS) because the government’s new income support schemes will replace up to 80% of workers’ normal monthly incomes up to £2,500 per month. People who normally earn much more than £2,500 per month (£30,000 per year) will see a bigger income shock than this, but the most recent data from ASHE (the Annual Survey of Hours and Earnings) suggest that only 10% of workers aged 20–29 were earning enough before the crisis to hit this cap (although it would affect 35% of workers aged 30–39 because they tend to earn more).

Households where the HRP is self-employed but can’t currently work could face a particularly acute income shock, at least in the short term, because the government’s income replacement scheme for the self-employed isn’t opening for new claimants until June (when claims can be backdated to March). So until then younger households who are normally self-employed will have to fall back on some combination of their own assets, Universal Credit, borrowing, and/or the generosity of friends and family members, although it’s hard to say how many people could be in this position.

There is some evidence to suggest that younger households are disproportionately concerned that they won’t be able to keep up with their usual cost of living: a recent survey by YouGov found that over a third (36%) of private renters aged 25–34 are either “not very” or “not at all” confident that they’ll be able to continue paying their rent over the next three months, which was a higher proportion than in any other age group.

The bigger picture

Although these figures already suggest that younger households are in a more vulnerable financial position than older ones are, there are also some other important reasons why they may be even less financially resilient than these data suggest.

Firstly, younger households are more likely to suffer an income shock than older households are in the first place because they are the age group which is most reliant upon labour market income. Older households are more likely to have their living standards buttressed by additional income from pensions or investment returns (including rent from additional properties they may own), whereas most younger adults are solely dependent upon the rate they can sell their time for in the labour market.

Secondly, we know that younger households are likely to have less freedom to reduce their expenditure in response to an income shock than older households do, because a higher proportion of their household budgets is taken up by relatively fixed “essential” costs such as housing, food and domestic utilities; IF’s research on this subject (published last year in collaboration with Yorkshire Building Society) showed that households where the HRP was under 35 devoted 63% of their weekly expenditure to essential costs, a higher figure than among any other age group.

By contrast, older households devote more of their budgets towards discretionary forms of spending, such as leisure and tourism, which they can cut back on much more easily without their living standards taking a hit. Although transport costs were also a big part of younger households’ budgets – and these have probably shrunk dramatically while the UK is in lockdown – this may be offset to some extent by costs associated with working from home (such as higher spending on electricity and heating) going up.

Thirdly, looking at the bigger picture, there could be a more insidious risk associated with younger households suffering large income shocks – if they are forced to rely upon their savings to tide them over during this crisis then that will retard their progress towards other savings goals, such as being able to own their own homes or accumulate money in a pension pot.

The impacts of this crisis on young adults’ personal finances could be felt for a long time to come.

Photo by Matt Reames on Unsplash: https://unsplash.com/@spookymatt

Help us to be able to do more

Now that you’ve reached the end of the article, we want to thank you for being interested in IF’s work standing up for younger and future generations. We’re really proud of what we’ve achieved so far. And with your help we can do much more, so please consider helping to make IF more sustainable. You can do so by following this link: Donate