The Labour Party saw it, and the Conservatives missed it: one thing in the recent election that really made its mark was the youth vote. Liz Emerson, co-founder of IF, explores the early signs of a significant shift

The exit polls suggested something was amiss and then the first results came in – large increases in turnout in predominantly university constituencies. As further results came in, turnout had not only increased in those constituencies but across the country.

Professor John Curtice, political scientist and polling expert, suggested that the swing to Labour was a little bit higher where there were more young voters, with turnout increasing in constituencies with more young people.

Crunching numbers

Lord Ashcroft’s polling suggested the Labour lead over the Conservatives was 49 points for 18–24 year olds, 36 points for 25–34 year olds, and 20 points for 35–44 year olds.

Then the latest YouGov post-election poll revealed that 66% of 18–19 year olds voted Labour, and likewise 62% of 20–24 year olds and 63% of 25–29 year olds.

Whatever the final figures are on the turnout, it is clear that young people have returned to politics. As Dr Phillip Lee, Bracknell Conservative MP, stated on national TV, “We saw the effect of the young vote on the doorstep.”

We at IF put it down to a generational response to the many injustices young people have had to face from politicians (of all parties) who have ignored their plight over the past ten years.

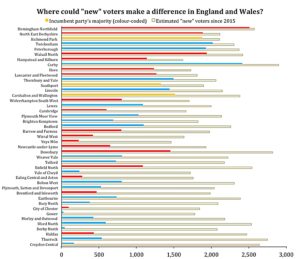

As a non-party-political organisation we could not show a preference for any political party, but we could highlight those constituencies where young people could make most difference. Our report identified constituencies where first-time voters could make most difference, as well as those where the MP’s majority was less than 10% of the number of eligible under-34s.

Student revolt

What we do know is that young people have finally turned anger, disillusionment and a sense of disenfranchisement into action.

Among students and recent graduates this could well be ascribed to the trebling of tuition fees, the removal of maintenance grants for the poorest students, the freezing of the repayment threshold, and a forthcoming interest-rate hike on student loan borrowing to 6.1% from September 2017. The final straw may well have been the parliamentary vote to allow universities to increase tuition fees by inflation annually until 2020.

As student debt repayments start to bite and young people realise they face an effective tax rate of 41% on pay over £21,000, national insurance of 12% and income tax of 20%, their voting power may come back to haunt more than just Nick Clegg, former Lib Dem leader, who lost his seat.

Getting their voices heard

On housing, the record for all political parties has been poor, both in terms of the delivery of new housing and help to tackle high rents, high letting fees and rogue landlords. Housing affordability affects young people, with more than three million having no choice but to return to the family home rather than striking out of their own like previous generations.

On jobs and wages, the young have suffered the most from poor employment prospects, zero-hours contracts and low wages, in spite of taking on the university debt their parents told them would help give them a leg up.

According to Owen Jones, this was the biggest shift in polling since Clement Attlee. “Here’s to Britain’s young,” he tweeted. “You were ridiculed. Patronised. Demonised even. And you may have changed history, whatever happens.”

This election politicians have learnt the hard way that the views of young people will need to be taken more seriously going forward and are now a force to be reckoned with. This is good for democracy, the country, and intergenerational fairness.

Image by Jens Johnsson: https://unsplash.com/@jens_johnsson