David Kingman looks at the final report from the Electoral Commission’s investigation into Individual Electoral Registration

Young people aged 18–34 were the group who suffered the largest decline in political enfranchisement following the switch to Individual Electoral Registration (IER) which was completed in December 2015, according to the final report from the Electoral Commission’s investigation into the impacts of this change.

Major changes

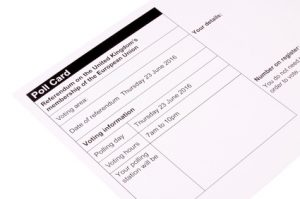

As most people are probably aware, the electoral register is the lynchpin of our democratic system: it provides the official record of who has the right to vote in elections and other democratic events such as referendums, and is also an important source of information for other administrative processes such as boundary reviews, jury service, law enforcement, credit rating and marketing. Your details have to be registered on it by a predetermined cut-off point before each election in order to be issued with a poll card which entitles you to vote.

Between June 2014 and December 2015, the government made major changes to how people register to vote. Previously, registration was undertaken at the household level, with the “head of household” providing the details required to register everyone who lived at a given address. Following the introduction of IER, individuals are now required to register themselves; for the first time they need to provide proof of their eligibility to vote, including their National Insurance number, date of birth and name and address, so that these details can be checked against other official administrative databases to ensure that people are being truthful.

IER is supposed to have several advantages compared to the previous system: it makes electoral fraud much more difficult; it reflects changes in family life, where the concept of a paterfamilias figure who can act as the “head of household” feels rather outdated; and it is supposed to make it easier to register as you can now do so online.

However, concerns have been raised that certain groups were disproportionately likely to disappear from the register following the changeover, particularly people who regularly change their address such as young people who are students or private renters. Unfortunately, these concerns have subsequently been borne out by the Electoral Commission’s own investigation into the impacts of IER.

Young people disenfranchised

The headline findings of the research were that the electoral register for parliamentary elections as it stood in December 2015 – the first month after the change to IER had been fully implemented – was 91% accurate and 84% complete, but “there have been statistically significant drops in completeness among younger age groups and socio-demographic groups more associated with the young such as private renters and recent home movers.”

Although the Electoral Commission concludes that the transition to IER did not have a statistically significant impact on the accuracy or completeness of the electoral register for the population as a whole, age and mobility (the frequency with which someone changes address) were found to be the two variables which had the strongest correlation with being missing from the register. Of particular concern was the lack of completeness of the register for people who had lived at their present address for less than one year, only 27% of whom were registered correctly. Given that many young renters change address frequently following the end of six-month assured shorthold tenancies, this underlines that they are at especially high risk of being disenfranchised.

This is particularly concerning in light of the one of the report’s other findings, which is that people who were registered correctly in December 2015 were significantly more likely than the population average to have voted in recent elections. Clearly, the causation could work both ways here: young people who are more politically engaged are probably more likely to make sure they are registered, but at the same time – given how many young people appear to be politically disengaged – erecting an additional barrier to voting could be especially damaging.

The Electoral Commission is keen to point out that voter registrations did rise significantly before both the 2016 local elections and the UK’s EU referendum in June, so it’s possible that many young people could have registered shortly before these votes. However, the overall conclusion of their report is that the new system misses out too many people to be sustainable in the long term. Their main recommendation is to call for a different type of register which “uses trusted available public data to keep itself accurate and complete throughout the year without relying solely on action by individuals.” That the Electoral Commission itself considers the new system to be so badly flawed should clearly be rather embarrassing for the government.